fernweh

/ˈfɛʁnveː/

farsickness or longing for far-off places

This next installment of the Fernweh discussions on the Blog was conducted with a friend of mine from Romania during last year’s spring quarter. It was—and is still—surprising to see how close our cultures to each other yet also so different. On top of sharing her personal opinions and knowledge on traditional Romanian clothing and the history that accompanies that, Sara also presented very recent fashion events in Romanian style.

I hope you can experience the same joy I did when I was first learning about Romanian culture. This will be my last Fernweh, but I hope to see you all in a completely different series. Bye!

What does it mean to you when I say “Romanian clothing”?

As cliché as it sounds, traditional clothing reconnects me with my home country and my culture. Moving around, I have struggled to find a sense of belonging, and traditional clothing has always represented a refuge for me. However, it is interesting to notice that it was not until I left home and objectively detached from my country that my traditional clothes disclosed unique information about my identity as a Romanian.

How would you describe the traditional clothing in Romania?

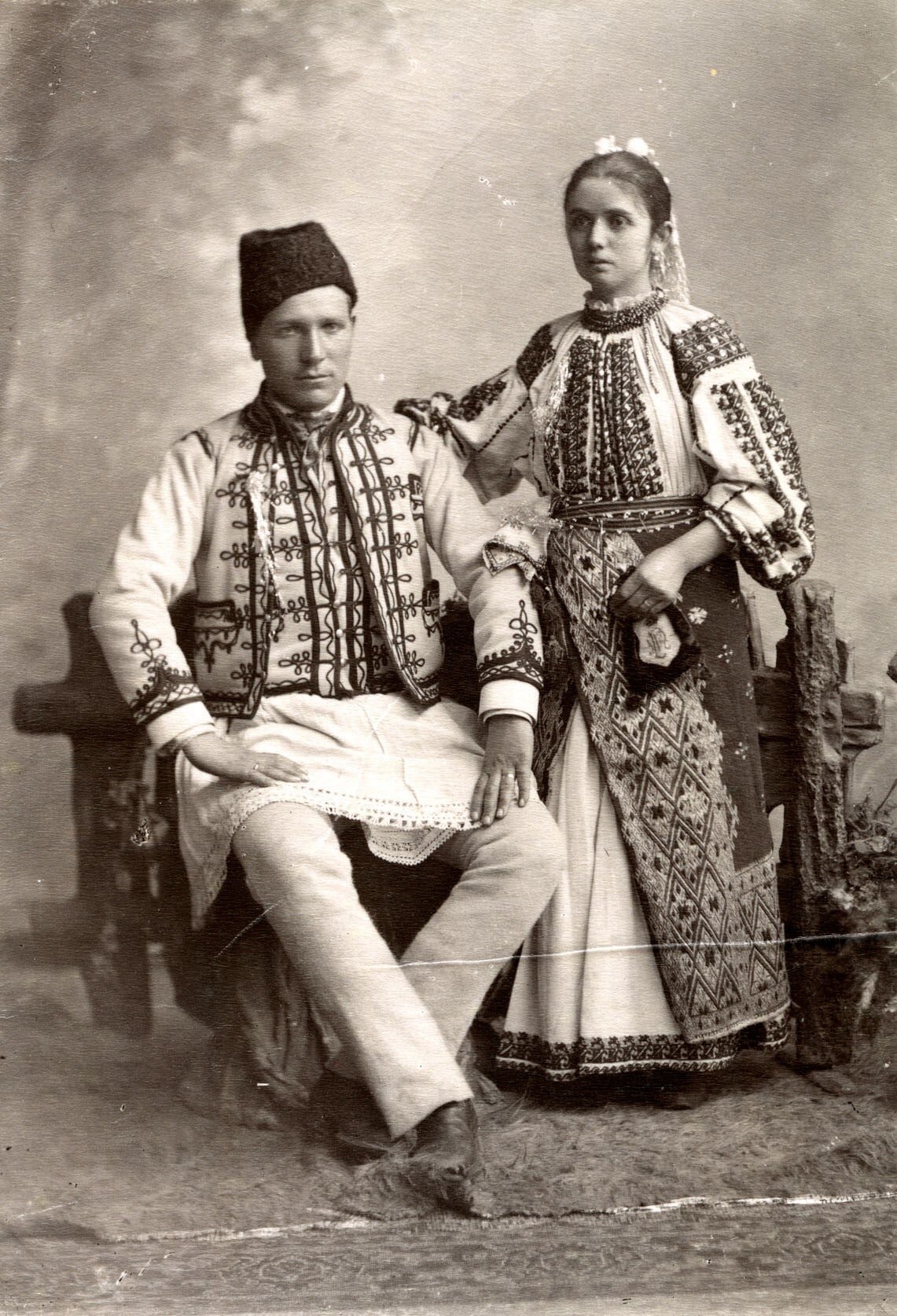

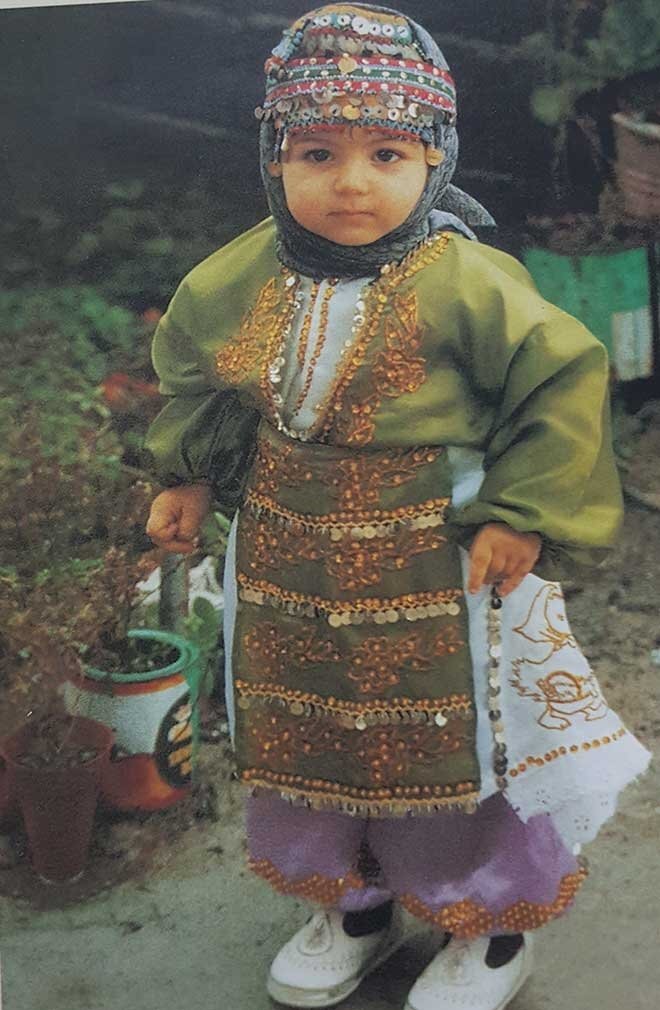

Handmade. Their origins go a long way back to the ancient Dacian civilization. A white shirt or blouse made from linen or wool is the basic garment for both men and women in Romania. Traditionally, men wear white pants, a white shirt, a hat, belt and overcoat. Women also wear a blouse similar to the men's shirts but longer. Skirts are woven with a pattern and often have embroidery and often are topped with a black vest. Women wear scarves or head coverings.

Image via

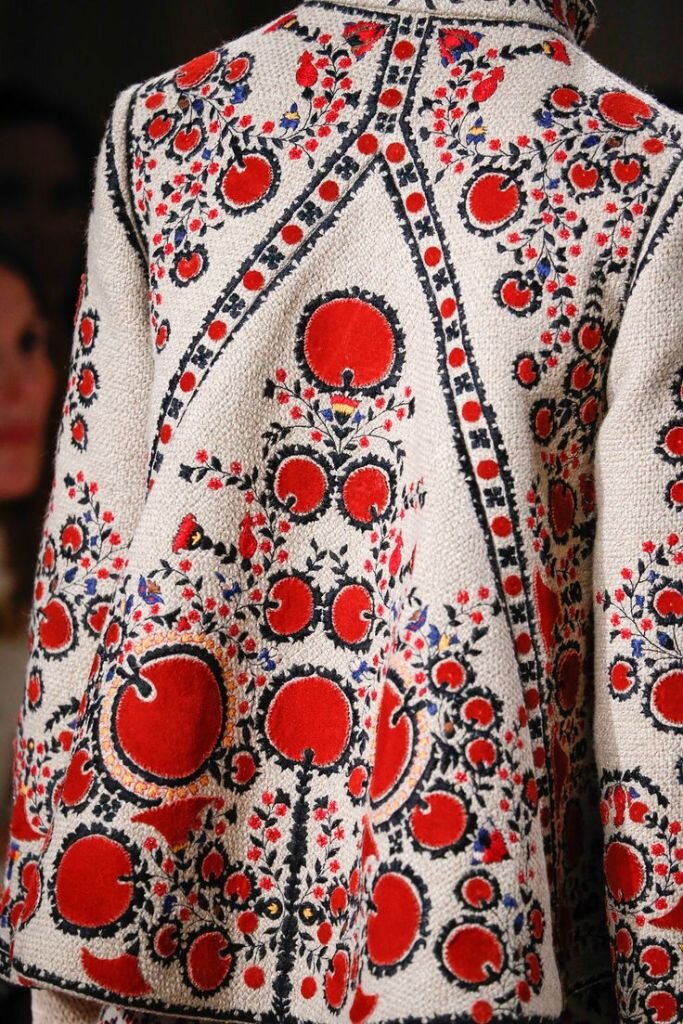

What today we know as the Romanian IA or “La Blouse Roumaine” represents the most representative clothing piece of the Romanian traditional ethnic costume. The first type of Romanian blouse is considered to have been born in Cucuteni Culture starting as early as the 6th century BC. The detailed and colourful hand-made embroidery always bore the weight of numerous popular Romanian motifs, patterns, sacred geometry elements and mystic symbols. No element was left to chance. Each one of them was embroidered for a very good reason as by itself or all together they were telling a story. A story of the women who wore the Romanian IA. They were directly linked with the traditions and specificity of the region the IAs were made. The cut, the embroidery and even the colours on the IAs had a direct connection with the region of Romanian where they were made. One might say the IA comprises the life and history of the people living in that region.

Image via

How would you describe today’s clothing? Are there any major contributions to fashion, such as designers, trends, labels, weeks…?

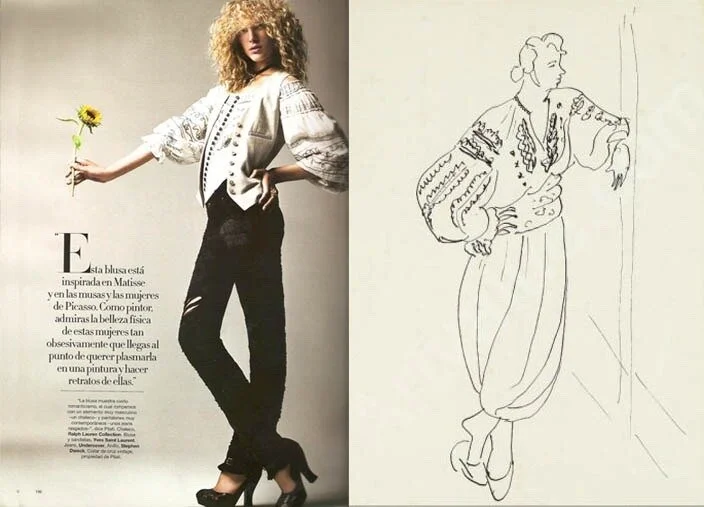

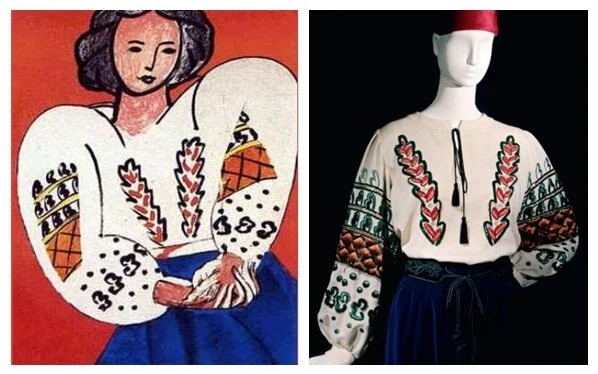

Yes, in fact it was Yves Saint Laurent, the world’s first famous designer, to officially introduce the Romanian IA into his fashion collection back in 1981 in Paris. Almost 50 years later after Henri Matisse finished his painting “La blouse Roumaine”, Yves Saint Laurent launched his autumn-winter haute couture collection. It was a homage to Matisse’s famous painting and as you can see below the resemblance is astonishing, yet you can easily spot the designer’s personal touch.

Image via

Image via

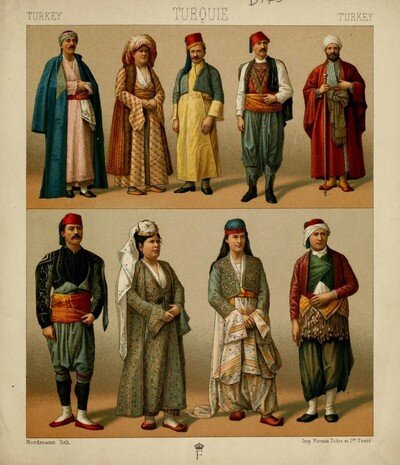

(Writer’s side note: It is worth mentioning Dior’s Romanian cultural appropriation discussion. In 2017, Romanian designers accused Dior for plagiarizing their traditional clothes and patterns to showcase on their fashion show—read more on this here)

Feature image via