From Italy to Harlem, the pain and rebirth of life comes forth once more in the art of the 2020s.

Read MoreThank You For the Music: Spring Awakening

Created by Alexandra Fiorentino-Swinton and a group of MODA Bloggers, Thank You For the Music started off as a Secret Santa style music exchange. Music connects us all, and what better way to peek inside someone’s heart than through our favorite tunes?

We each commented on a song that reminds us of what’s to come: springtime. We exchanged of songs with each other and allowed our fellow bloggers to write about what it evoked. After a tumultuous winter—literally and figuratively—it’s time to look forward.

Vivian Li’s pick: Mogli, “Wanderer”

It took me a while to find a song that perfectly embodies spring, so I started playing my entire Spotify library on shuffle and my roommates said no to every song (understandable because we only ever agree on LDR). Miraculously, we all picked this song before Mogli even started singing, so it was love at first chord. “Wanderer” is originally from my “morning ritual” playlist because I like how calm, hopeful, and free-spirited it feels. It has the power to cleanse my mind and get rid of negative thoughts, but I completely forgot about this song because I'm currently going through a hyperpop phase...

~

Oh the wind in my hair

It sings my song

To be a wanderer

And to go on

~

Anyways, I don't know how to write about music, but everything about this song captures the energy I want to have for spring. The wind will no longer be harsh and cold; it will caress my face with warmth and the air will smell fresh. I will listen to this song while walking down S. Woodlawn Ave on my way to school. It makes me hopeful thinking about how I can let go of past worries and live freely.

Nadaya’s Take:

I’m a visual person. As soon as I heard the opening chords of this song, I just had to see if there was a music video. And there was… kind of! A lyric video of Mogli’s expeditions: walking along the beach, sticking her head out of the passenger-side window of a car, being a wanderer.

Something about this brings me back to being thirteen, when all I wanted to do was travel. Does anybody else remember those instagram accounts, those travel bloggers who’d go anywhere all the time? It incites such a specific, youthful, spring-time nostalgia.

“To be a wanderer and go home…”

What is home, really? What homes can I make this spring? In the comfort of my bed, windows open to hear the birds chirping. On the slippery rocks of Lake Michigan. Underneath a bed of sand on Oak Street Beach. Among friends on the grass of the nearest park. Vivian said it best. There’s something about spring that makes you want to live freely and begin again.

“Making way to new beginnings…”

EJ Song’s pick: Dumbo Gets Mad, “Indian Food”

I discovered this song during finals week of fall as the weather was getting colder and colder. I was sitting in a Harper cubicle with friends, and as I sat there enjoying their company and listening to the psychedelic synths and chimes of the song, I remember seeing sunlight coming through the Harper windows and thinking how warm I felt in that moment.

This song uses a wide range of instruments to create this surreal, almost alien-sounding orchestra playing in the background. At one point, there’s an erhu solo - and I’m always skeptical of white people using Asian instruments in music, but I have to admit that this erhu feature bangs. I’m saving this song to enjoy for the spring when the sunlight comes back. A psychedelic rock song about good food and love - what more could you want?

Ivana’s Take:

I didn’t recognize the song or the artist when this was recommended to me, so I genuinely could not predict what I would be in for, other than maybe indie song, but I was pleasantly surprised by what it was. In seasonal terms, this song sounds to me like that hazy convergence of spring and summer towards the end of the school year. It reminds me of car rides with people you love, as the sun sets and bathes the skyline in gold.

I was especially pleased by the erhu solo featured at the bridge of the song as the singer’s voice fades in the background, in a delightful synthesis of psychedelic rock sounds and an Asian instrument in a way I haven’t often heard in Western music. And, it scratches my brain just right. Do yourself a favor and add this song to your playlist.

Kája Muchová’s pick: The Avalanches, “Since I Left You”

The first time I heard this song, was two years ago, the start of spring, when covid was just a temporary excuse to stay at home and make whipped coffee. During that time, I loved to go on long walks around my house, listening to different artists and albums. This song really caught my attention. I was certain I never heard it before, but it also seemed so familiar.

With that in my mind I proceeded to listen to the entire album, conveniently named “Since I Left You”, immersing myself into an incredible music experience. Every song fluently followed the next—I had no idea when one ended and the other began. This for me was one of the most memorable music experiences and so I think it is only fair to recommend the first song that started it all.

Honestly though, I think everyone should listen to the whole album. It will certainly give you a very unique, transformative and refreshing experience, something that all of us really need after an exhausting and tiring winter.

Vivian’s Take:

Let me begin by saying I LOVE this song and have been listening to it nonstop. It makes me nervous writing about such a timeless classic, but I will try my best. The song feels like a conversation with someone intimate. It sounds poignant but hopeful. The vocals are simple but leaves a strong impression, and I can say without complain that it has been stuck in my head for the past month. Perhaps what is so powerful about the song is how universal the feeling can be. It can be letting go of a bad relationship, a toxic friendship, or a stressful obligation. Once you let go, you realize there is so much happiness around you.

Since I left you, I found the world so new.

I can even say the same to Chicago winter, because I absolutely hate it but would not trade it for anything in retrospect. How do we appreciate the warm sunlight and bird songs of spring without the harshness of winter? One time I found somebody’s handwriting at a corner booth in Medici’s, scribbled on aged wood with black marker: se faire printemps, c’est prendre le risque de l’hiver. I never bothered to look up where it comes from but the quote stuck with me, and turns out it is Antoine de Saint-Exupéry!

Ivana Del Valle’s pick: Circo and iLe, “Me Saben a Miel”

Ivana’s Take:

Chicago is extremely different from the tropical island of Puerto Rico I grew up in, and moving here for college honestly made me a little scared that I would lose my culture, since, for me, a lot of it comes from casual interactions with it— the traditional music played in local stores, the food I ate at home, the slang, even the way people dress and greet each other. I wanted to stay in touch with home in simple ways that didn’t feel forced, and one of those ways was listening to local Puerto Rican artists, such as iLe. The music iLe composes is deeply poetic, political, bittersweet, and unapologetically Puerto Rican, adding modern spins on more traditional genres that are often overshadowed by reggaeton, such as bomba, plena, salsa, and bolero.

“Me Saben a Miel” is originally from the Puerto Rican band, Circo, but was recently re-released featuring iLe as the lead vocals. The song sounds like warm, spring evenings spent in the mountain countryside back home, rocking in a hammock and joined by the sweet chirping of coquís. iLe’s voice beautifully flows in tandem with the guitar and saxophone instrumentals in a way that almost feels like from the nostalgic past, and, as the name implies, certainly “sounds” like honey.

I would definitely recommend this song as a starting point to anyone interested in exploring different Latin/Puerto Rican music genres, or anyone simply wanting to listen to something new.

Kaja’s Take:

Reading the title “Me Saben a Miel” I did not know what to expect because I realized that I don’t listen to a lot of Puerto Rican music. The last Puerto Rican song I heard was in my Spanish class in high school and it didn’t really grab my attention.

However, right when I pressed play to listen to this song, I was surprised by how much it matched my current music taste. In fact, its intro reminded me of my favorite band Crumb. However, I have to note that “Me Saben a Miel” is certainly a happier version of anything I would listen to from Crumb but despite that it gives me the same feeling of calm and dreamy happiness.

The guitar backdrop music with layered vocals screams spring which I know might sound very vague but there is no other way to describe it. You will understand when you listen to it, which you certainly should!

Nadaya Davis’ pick: Blood Orange, “Saint”

Blood Orange always makes me feel spring in living color, and I think the reason why is quite simple—Dev Hynes is a musical genius. The song is a combination of sweet, choral-like vocals and the airiest of instrumentals, the musical personification of an open window on a beautiful, city afternoon.

The song points towards a return to sainthood, a return to a place of virtue, for brown and black youth in particular. The music video, too, reflects on what sanctuary can be. In Hynes’ case, he has a jam session in his studio while his people exist besides him—resting, smoking, laughing, eating, and just being together.

I’ve often caught myself wishing Hynes’ music could be the score of my own life; it’s nostalgic and familiar, stirring up a cosmic force inside of me that breathes, let’s live! This Spring, I’m hoping to grant myself the pleasure of leisure, of existing without burdens.

EJ’s Take:

Starting with the smooth sound of the saxophone, this song is filled with soothing but vibrant tones and energy. A lot of the instruments featured in the song, like the sax, cello, and keyboard, make the sound feel classic and timeless; the brass also reminds me a lot of 90s R&B.

A huge part of this song is a celebration of blackness - the chorus, “Your skin’s a flag that shines for us all/You said it before/The brown that shines/And lights your darkest thoughts”, speaks to this in such a poetic way. I wasn’t really paying attention to the lyrics the first couple times I listened to it, but they added so much more depth to the song.

And Nadaya said it best - the song and music video perfectly incapsulates the sense of community and compassion that come together with music, company, and good spirits. Saint is perfect for so many different moods - it has the liveliness to get you through the worst, grimiest p-sets, the calmness for a quiet moment of relaxation, the energy to blast on your speaker while you sit with friends on the quad.

Winter Quarter... I'm So Done With You: A MODA Blog Playlist

Winter quarter, winter quarter. Where do we begin?

We’ll let the music speak for itself. Check out some tunes curated by MODA Blog to wrap up the quarter—we’re nostalgic, we’re gloomy, we’re over it, we’re understanding ourselves, we’re pumped, and we’re happy we made it.

Nadaya

Dreamer Isioma - I’m So Done With You

Winter quarter isn’t the one who got away: it’s the one you want to forget. I’ve been playing Isioma’s Goodnight Dreamer since its release in late February, and while the songs themselves instill some longing for the spring and summer, this track is just so over it. So am I.

Life don't treat me right

So I go out every night

Dirty dancing like the 80s…

Aashana

SAINt JHN - Sucks To Be You

The album is titled “while the world was burning,” but my world was freezing. Just started listening to SAINt JHN at the start of this quarter and this is now my favorite PR song at the gym.

“She said she believed in me just keep on goin',” from me, to me. We made it!

Wonyoung

James Blake - “Meet You In The Maze”

Sometimes, one’s passion can become all-consuming to the point that one begins to lose sight of oneself and reality as a whole. As Blake sings, “From November through 'til now,” I also had found myself in a “maze” of my own creation –– no longer pursuing my art, but instead becoming the pursued. In those times, it’s good to remind oneself that such endeavors are means to an end –– that end being the derivation of pleasure and excitement in my life and the lives of those around me.

BROCKHAMPTON - “BLEACH”

Perhaps I can owe the recent renaissance this overplayed 2017 song has had in my playlists to the comfort bred by its familiarity and its nostalgic “emo high school boy” charm. Am I listening to “BLEACH” alone at midnight because I too “feel like a monster, feel like a deadhead zombie”? Or am I just listening to it because I’m still in denial of the fact that BROCKHAMPTON is going to break up after Coachella? The world may never know.

Elliott Smith - “Angeles”

Apparently it’s now cool to listen to Elliott Smith. At least according to the trendy TikTok e-people who probably also just discovered “Here Comes The Sun” last week, and Morrissey the week before that. As somebody who has been listening to him from a young age, I feel foolishly possessive of Smith, and what better way to gatekeep than re-listen to his whole catalog so that I can tell everyone that I was “not like other girls” before they were?

Anna

Aurelia

girl in red - “dead girl in the pool.

The perfect mix of catchy but also slightly sardonic, this song really fits the laid back and moody vibe of Winter Quarter. It got me through a lot of winter quarter sadness and is perfect to play in the background.

CORPSE- “agoraphobic”

Unlike his other songs, agoraphobic offers a soft lo-fi beat perfect to vibe to while writing your essays or cracking down on a p-set.

Album Review: Voyage

We all know ABBA in some form. If you don’t… you do. Trust me on this one.

Image Via

Since their conception in 1972, ABBA has found a way to permeate pop culture and media through their distinct, almost irreplicable music—a vibrant mix of pop, pop-rock, and disco. Unafraid to tackle odd subjects, such as kissing your teacher or happy vacations to Honolulu, their music spans far beyond chart numbers. Their song “Waterloo” having won the Eurovision song contest in 1974, and band members and songwriters Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus having written the successful Broadway musical Mamma Mia! using their own discography as the basis for the soundtrack. And currently, the band is developing a stage performance in London that employs VR performance-capture technology to display the band in their prime via digital avatars, de-aging them back to 1979.

So let’s just say, ABBA found a way to culturally persist.

Now, nearly forty years following their last album The Visitors released in 1981, the quartet has returned from a four-decade hiatus with new music. Ready to embark on another musical journey with their latest album Voyage released November 5, 2021.

Image Via

For a long-time superfan of the Swedish sensation like myself, the release of Voyage was and still is my most anticipated release of the year. After marinating in this new music for a bit, it’s time I pull up my musical bootstraps and take a journey into this new release from my favorite artist, digging in and giving my review of the long-anticipated return of ABBA.

The first track and one of two promotional singles for the album, “I Still Have Faith in You” commences the band’s return to music with a ballad. The introspective lyrics, written by band member Benny Andersson, focus on the current of time and how faith and trust remain despite the separation of time or shared animosity, reflecting the trajectory of the band’s relationship since the 1970s. This connection to the band is alluded to in the chorus with the lyrics: “We have a story/And it survived/And we need one another/ Like fighters in a ring/ We’re in this together.” With a beautiful piano track, this anthemic song commences their return with the reminder that ABBA will remain together despite distance or separation. Also, this song makes history as the first ABBA song nominated for a Grammy award, nominated for Record of the Year.

ABBA detours from their typical sound with “When You Danced With Me” leaning into Nordic folksong for inspiration. The reminiscent song details someone speaking to a long-gone lover, asking if they miss the times they danced together at the Village Fair. However, the Nordic folk sound gives this reminiscence an optimistic swing, making their curiosity about their lover almost supportive. This contrast is what I find makes this song an ABBA song. The focus on heartbreak and longing underscored by optimistic drums and synth presents the downfalls of love, such as losing a lover, as a moment of profound affection.

Suddenly, it’s Christmas time. The album shifts tonally at this point with the third track, a Christmas song of all things. I can understand why there is a Christmas song, as the album was released just before the holiday season, but the song itself is lackluster. On their first voyage into the Christmas music market, the song “Little Things” sings of Christmas mornings and the bursting sounds of ecstatic children as they giggle and yell of gifts from Santa. A simple piano track with an outro sung by a children’s choir, the hymnal song is considerably run-of-the-mill by comparison to other Christmas songs of the same nature. There is nothing original to it, riddled with holiday clichés and a simple melody that fails to do anything musically authentic compared to other songs by ABBA and other Christmas songs. This song is also tonally inept compared to the rest of the album, pandering to a new holiday audience without considering its own originality beforehand.

In the same vein as “So Long” and “All Is Said and Done” the fourth, fifth, and ninth tracks on Voyage can all be summarized as rock-piano stylings that reel you with addictive melodies laced with catchy lyrics. “Don’t Shut Me Down” and “Just a Notion” and “No Doubt About It” all follow what I consider—the ABBA musical formula. Using a set of exciting narratives or ideas to write fun lyrics underscored by well-styled piano, drums, and synth. The result is a catchy song that anyone can enjoy. This formulaic but authentic means of creating music is uncanny in its ability to make chart-topping sounds.

Voyage thus far has introduced new outlets of ABBA unexplored in past albums: new genres, sounds, and even subject matter. However, the album’s latter half returns to the introspective realm with the sixth track, “I Can Be That Woman.” The ballad is the story of a woman returning home, viewing her life through the contemplative lens of her failures with sobriety and the changes to her life in her struggle to overcome addiction. In a commentary for Apple Music, band member Björn Ulvaeus said this about the song: “Only we know what is fact and what is fiction about our life experiences together. It’s a kind of freedom that you get. With 70, you get that freedom.” This song, while musically simple, packs a narrative punch much harder than the typical focus of ABBA.

From this point, the following two tracks maintain this somber subject matter established with “I Can Be That Woman.” Almost tangential to “I Can Be That Woman” the seventh track “Keep An Eye On Dan” deals with familial change, marital issues, and personal struggle. In contrast, “Bumblebee” reflects on catastrophes of climate change. Both songs present a new maturity to ABBA not seen in the past, upheaving the process of traumatic personal struggle and even treading into the waters of social commentary with “Bumblebee.”

Image Via

Voyage by ABBA consists of the old and the new. Nostalgia is peppered throughout the album, encouraging fans to reminisce in the sounds of ABBA we’ve come to recognize. Yet, the album welcomes a new maturity, revealing an ABBA redefined by the time separated from the spotlight and each other. Voyage at its core is the story of ABBA’s 40-year long journey after The Visitors. We, as the listener, are brought in to hear what changed and remained the same, to take a voyage through the experiences, the hardships, love, and loss of these four individuals after one of the most successful careers in music history, and to see where this career led them after that. While this album is far from perfect, it is the journey of the artistic transformation of ABBA as a band parallel to the personal developments of Agnetha, Benny, Björn, and Anna-Frid, as people.

Thumbnail image via

Album Review: Whole Lotta Red

Image via

There is perhaps no musical artist in today’s cultural scene who can deftly shapeshift with more volatility than Playboi Carti. His ability to sprint in one direction, stop on a dime, and pivot to another in any number of wild, unforeseen ways, has contributed immensely to his mystique. Only a few months after releasing his 2018 album Die Lit, Carti began recording his next, which he proclaimed would be a more “alternative” and “psyched out” project that would propel his sound into uncharted territory. A few months later, in May 2019, fans leaked several songs he was looking to include on the album on YouTube, SoundCloud, and TikTok. Unreleased tracks such as “Pissy Pamper,” “Opium,” and “Taking My Swag” racked up millions of listens across myriad platforms, driving Carti to remake the album from scratch — yet another testament to his improvisational virtuosity as an artist. Then, in April 2020, Carti dropped “@ Meh,” which he purported to be his upcoming album’s lead single; in one more bewildering about-face, he would ultimately exclude the track on the final project.

Thus, it is only fitting that Carti’s relentless versatility is just as prominently displayed in Whole Lotta Red as it is in the whirlwind of events that culminated in its creation, and the opening track, “Rockstar Made,” functions as a potent overture to the album’s twisting turbulence. In the track, Carti’s vocal adeptly careens with cataract force from his signature “baby voice” — imparted within a lighter, higher register that is equal parts delicate and shrill — to a darker, more serrated tone laced with intentional straining and cracking. His chameleonic acrobatics are amplified tenfold in their visceral extravagance against a bold backdrop of clipping 808 instrumentals and menacing minor synth lines; the effect of Carti abrasively rasping out every last drop of sound from his being, as if his contorted vocal cords have been eviscerated from hours of screaming the song’s lyrics, transcends performance and comes to embody the artistic experience. “Rockstar Made” thus exemplifies the most enthralling aspect of Whole Lotta Red: it masterfully explores the multitudes of complex identities and sounds that Carti adroitly weaves his work with, paving the way for a musical masterpiece unlike any other.

Image via

The album’s first three tracks — “Rockstar Made,” the Kanye West feature “Go2DaMoon,” and the Gucci Mane-inspired “Stop Breathing” — showcase Carti at his rawest and roughest. He hisses, “I take my shirt off and all the h*es stop breathing,” yet he sounds as if he is the one who is on the cusp of losing his air, especially as he gasps out arresting lines like “Ever since my brother died / I been thinkin’ ‘bout homicide.” Carti’s trademark minimalistic writing — with choruses and hooks as repetitive as a Philip Glass string quartet — both contrasts with and complements this dramatic delivery style. Instead of unwittingly falling victim to meaningless tautology, Carti’s lyrics daringly lean into repetition with the conscious intent of instilling every single reiteration of every single syllable with an ineluctable dynamism. The risk pays off in spades, as the high-pressure tracks on Whole Lotta Red crackle indelibly with eclectic energy.

Image via

Just as Carti begins to lull the listener into his rhythm with the album’s opening trio of tracks, he abruptly yanks us into a different dimension — a grating outro filled with rasped repetitions of “whet” suddenly segues into “Beno!”, which opens with a cutesy and whimsical synth descant that would not sound out of place playing through the aisles of a candy store. He shifts his aggressive flow to a playful lilt, donning his idiosyncratic “baby voice” to maneuver through more metrically meticulous moments. Despite their lyrical complexity, lines like “All black 2-3, LeBron with the heat / I was just in Miami in the Rolls Royce geeked” begin to sound like simple playground chants and nursery rhymes because of the breadth of Carti’s sonic inventory. As the album progresses, we are plunged even deeper into this funhouse tour of musical madness. The sinister “Vamp Anthem” warps Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” into a harsh trap beat; the saccharine chord progression and pulsing instrumental of “Control” evoke the sound of early 2010s dance-pop; soft samples of Bon Iver lend a transcendental tranquility to the album’s closing track, the indie folk-influenced “F33l Lik3 Dyin.” Yet, as we are tossed asunder by the hurricane that is Whole Lotta Red, we never quite feel like we are losing sight of the album’s core meaning and sound — it is the perfect storm, an illusion of chaos orchestrated with scientific precision by our maestro.

Whole Lotta Red reaches its most immaculate heights when Carti acquiesces to the music’s hypnotic power, letting his innermost words and feelings spill out of him, unbridled and unchained. “Slay3r,” which features exquisite production by Juberlee and Roark Bailey, cradles Carti back and forth with its carefree and cartoonish ambiance, and he playfully responds with uncharacteristically jocular refrains of “Whole lotta mob sh*t / Whole lotta mob, whole lotta mob sh*t.” The juxtaposition of such a jaunty sound with the track’s devilishly dark subject matter and inspiration — the song pays homage to the thrash metal band Slayer — palpably demonstrates how twisted Carti’s sense of irony becomes when unleashed in full force. As listeners, we are even treated to an exploration of his vulnerable side; on the deceptively chill “ILoveUIHateU,” Carti pours out, “I mix all of my problems and Prometh’ until I roll on my death bed / Don’t get close, uh, baby, don’t get too close.” This riveting confession — of his potentially lethal drug use, of his fear of emotional intimacy and availability, of his awareness and deliberate ignorance of his self-destructive tendencies — paints a different picture of Carti than his “rockstar” songs do. We have peeled back the façade of Carti the artist to reveal Carti, the human.

Image via

The album reaches its zenith at the start of its final stretch with the track “Sky,” which is an ode to substance abuse and its escapist utility. After a disorienting intro that sounds vaguely like video game boss music, Carti comes in on the chorus with a mesmerizingly restrained sound that still sounds like it is on the verge of losing control. After tenuously riding the beat through the track’s opening, Carti hits its next section, which fittingly begins with an invocation to “Wake up!”, and he loosens up and begins to derail in the best way possible. Carti’s flow loses its smooth sheen and slowly becomes erratic and syncopated, navigating through intricate polyrhythms and oscillating between being behind the beat and being in front of it. He delivers lines like “Can’t f*ck with nobody, not even my shadow / I got on Ed Hardy, she got on stilettos” with a captivating fiendishness that puts the listener on edge in spite of the track’s relatively tame vocal and dreamy Travis Scott-like sound.

Whole Lotta Red garnered intensely polarizing reception upon release, with many diehard Carti fans proclaiming that the album is too splintered and possesses no particular unifying sound. While these traits may be undesirable in the rap mainstream, they are precisely the unique traits that give Whole Lotta Red its je ne sais quoi. The album is nothing short of manic and unhinged; it is a treacherous labyrinth, filled with everything, from Baroque polyphony to Atlanta hip-hop, and elevated by the incomparable temerity of Carti’s experimental performance. As he expresses in “Punk Monk” with the declarations, “I just worry ‘bout me” and “I don’t rap, I write poems,” Carti deeply values pure authenticity and innovative brazenness, and his new album reflects his commitment to keeping his head down, blocking out the noise, and carving out his own path in the rap industry. Whole Lotta Red stands by itself in today’s popular music landscape as a generational work of transcendent genius, unparalleled in its inventiveness, and listeners would do well to look past the smoke and mirrors of Carti’s carefully constructed madhouse to unearth the deeply emotional richness of his work.

Image via

Featured image via

The Repackage: The Reup: The Moonlight Edition

“We love to milk it,” Dua Lipa told Billboard late last year. Certainly, Dua has earned a reputation for dragging out her album eras for as long as possible. Her debut, self-titled album came with plenty of singles, remixes, and a “Complete Edition” with an additional three new songs coming at the end of the album’s cycle. Surprisingly, her sophomore album campaign has somehow put her first effort to shame.

Within the past year, Dua has released a standard (12 track) album, a 17 track long remix album with The Blessed Madonna and various high-profile collaborations, five singles with music videos and distinct single album compilations, three high-profile collaborations (Un Dia, Fever, Prisoner), and a live-streamed concert. And it has all culminated into her latest release—Future Nostalgia: The Moonlight Edition.

In addition to a review of the new songs, it felt appropriate to also take a step back and understand why Dua and deluxe editions have become a polarizing topic.

The lead single for the Moonlight Edition is without a doubt not bad. However, “We’re Good” fails to move Dua in any particularly interesting direction. Much like her debut, the production is crisp and contemporary but doesn’t leave a mark. The trap beat and chill guitar contrast Dua’s husky vocals nicely, but it is neither futuristic nor nostalgic. Juding from interviews, it is clear that Dua was aware of this, comparing her anxiety about releasing it to the fear she felt before releasing the incredible “Don’t Start Now.” Whereas the latter was indeed a leap in sound for Dua, it was interesting and intricate enough to build into the hit that it is now. Will this new single do the same? It is possible that the laid-back, dare I say, basic trap undertones may propel it up the charts. Dua’s fears are unfortunately not entirely misplaced.

Back on track, “If It Ain’t Me” features a now-signature Dua bassline and catchy breakup hook as she sings, “I fill the floor with my sequin tears.” Less love-anxious and more in charge, “That Kind of Woman” is Dua at her retro best. The mid-tempo track features all the right synths and sporadic synths as Dua assures her future lover that she won’t be “one of many.” Things take an interesting turn for the final new track as rapper JID intros “Not My Problem”. Funky and crass, the track is quite the statement proclaiming, “if you’ve got issues, that’s your problem!” I am willing to defend the track on the ground that it has character and still feels like a throwback, although it is arguably not on the same quality standard as even the divisive “Good in Bed”.

The four new tracks are interspersed with the collaborations Dua has released throughout the year. The seductive, European beat of “Fever” and Olivia Newton-John's sample on “Prisoner” do a good enough job to fit the theme of the original record. On the other hand, ending the new edition with the Latin American breakup track “Un Dia (One Day)” is a head-scratcher. This leads us to the bigger question--what was the point of this Moonlight Edition?

While Dua has been promising a “Side B” for months now, it is hard to argue that three new tracks fit the classifications for a “Side B” release. It seems clear that the standard version of the album was short and compact for a reason; Dua had a clear artistic vision for the record. Is this new edition simply a money-grabbing move, or does it still hold the artistic merit the original record holds?

I am going to have to do some assuming in terms of Dua’s motivations in order to defend the new edition, but it stands to reason that although it is not an entirely cohesive addition, The Moonlight Edition is a continuation of the Future Nostalgia Era in its magnitude of content and artistic exploration for Dua.

We have certainly not seen such a thorough and detailed rollout from a pop artist since the breakouts of Lady Gaga and Katy Perry. The past year for Dua has demonstrated that she understands the value of having both a striking visual identity but likewise the confidence to switch it up. The sheer amount of releases and performances, particularly in the context of the pandemic, is second to none in the current pop music industry. It is no wonder that past icons like Kylie and Madonna have praised and collaborated with Dua. Thus, the new edition is simply a continuation of the past year, with more space-themed photoshoots and nostalgic music videos. Although “We’re Good” may sonically fit the record, the Titanic-themed music video seals the deal.

Image via

If we are comparing Dua to past artists, it also stands that she is certainly not the first to reissue an album. Nearly two years after its release, Katy Perry repackaged Teenage Dream into The Complete Confection with three new songs and a few new collaborations. While Dua’s rise to prominence has often been compared to Katy, this latest release does parallel the glorious pop era that was Teenage Dream, even if winding down in a similarly confusing note.

Original image via

Although deluxe editions were standard among pop artists, they have slowly faded away, most likely since those editions were always pushed by the labels more than the artist. However, as labels continue to try and maintain profits in a new streaming world, these deluxe editions are cropping up as delayed reissued editions. Aside from Dua, both Selena Gomez and Ariana Grande have released deluxe versions of their latest albums months after their initial release.

In the case of Ariana’s Positions, a similar thread of disappointment from fans has cropped up, wondering why the songs are so short or not all that special compared to the standard tracks (and at least Gomez and Dua provided new covers for the new editions). Had the deluxe edition come at release, it is likely that most people would not have cared, simply understanding that they are extra songs. The same reasoning appears to apply to Dua; feeling letdown comes more from the hype that is created by waiting to release the songs, rather than from the actual quality of them.

Dua’s Future Nostalgia: The Moonlight Edition presents us with a special mixture of both pop excellence and the pitfalls of the music industry. For one, the reissue may seem unnecessary to many people, especially in an era where the experience of an album has decreased in favor of singles. It is, however, a callback to the icons of pop that understand the power of creating a fleshed-out and consistent era. There is great attention to giving fans a lot of content, of which even the meh quality is great. I will not say that adding some collaborations to the album is simply a grab for more streams, but at the same time, Dua is having to wade through a more unstable sea of streaming and charts. If having the most-streamed album by a female artist in Spotify history, and Future Nostalgia out streaming others in 2020 is any indication, we should let Dua milk her eras for as long as she wants.

Thank You for the Music: MODA Blog's Collective Healing Playlist

When I read (and listened to) Alexandra’s first installment of this series, I thought about how her words very wisely captured my feelings regarding the situation we’re all in. Winter quarter is always the most challenging term, and it is overwhelming to have to face the stresses that come along with it on top of the trauma and anxiety that many of us have had to deal with over the past year. Beyond that, many of us have had to adapt how we heal, now that it’s more difficult to see each other. Beyond just an article, Thank You For the Music exists as a way for us here at MODA Blog to heal collectively through the exchange of art and music. So for any of you going through a lot right now, we see you, and we’re here to share with you some of our favorite pieces that have pulled us through some of our toughest times:

Andrew Chang: Bonnie Tyler - Holding Out for a Hero

Admittedly, I first heard this song while watching Shrek 2, and yes, I’ve stanned it ever since. There’s something about that rapid beat and that choral backdrop that just makes me want to get everything and anything done for the day. Winter quarter is always a rough time of year for me, and with the pandemic going on, I think I’ve been holding out for a hero for quite a while. Part of me wonders if one of the song’s powers is its capacity to convince singers-along to confess to needing some help, while concurrently convincing them that they can be the hero they’re holding out for.

It’s actually wild how long this song has been following me—from when I first heard it at the tender age of 7, to its cover on Glee, to appearing on the soundtracks for Detective Pikachu and WW84, Bonnie Tyler’s feel good song seems to always be there to remind me that sometimes I need a hero, and sometimes I can be the hero that I need oh so badly.

Denise Ruiz’s Take:

“Holding Out for a Hero” is the type of song that makes you want to run a marathon, climb a mountain, and finish your BA thesis in one afternoon. This is a bop that will get your heart racing and keep you motivated, making the song exactly what I needed to listen to this weekend. I personally love music that makes you feel like you could take on the world.

Fourteen years ago, Shrek 2’s “Holding Out for a Hero” moment defined an entire generation. It’s also special for me since it reminds me of my first summer in Chicago when I watched it with close friends.

And since we are in the middle of midterms, we could all use a hero right now!

Henrique Caldas: Only Girl (In The World) - Rihanna

“Only Girl (In the World)” is THE song that made me fall in love with music. Some people may judge this assertion as tacky, but something clicked inside me when I first heard it. I don't know what it was, but Rihanna's voice and its passionate, energetic beats enchanted me from the get-go. At the time, as an 8-year-old Brazilian kid with little to no knowledge of English, I could not understand the lyrics. But it didn't matter because, from then on, a genuine love for music developed inside of me—which for some reason also awoke in me a fondness for dancing. Nowadays, pop and EDM are still my favorite music genres, even if I listen to a wider range.

"Only Girl (In the World)" has the most nostalgic power of almost anything in my childhood. And because of the song's importance to my past and to my love for music, whenever I hear it, I am transported into a state where I tap into this lust for life that music brings me whenever I am down.

Clara Herf’s Take:

It's pretty hard not to love Rihanna and her diverse sound. She just can't disappoint, and on that note, can she please drop the new album!! This song, in particular, is energetic and just makes you want to dance. Simultaneously, it also reminds you to demand the respect and love you deserve. Don't let anybody treat you like your secondary or not good enough. "I want you to make me feel like I'm the only girl in the world" emphasizes the importance of being in a relationship that is genuine and makes you feel special. This song is a reminder to us all that we deserve to be loved.

Clara Herfs: The Climb - Miley Cyrus

This song hits different. I think it's my go-to song for when I'm overwhelmed or when I feel like giving up. When I was little, I was the biggest Hannah Montana fan. I had the blonde wig and everything. This song especially just reminds me to keep going and to keep fighting and that yes, times get rough and yes, "there's always going to be another mountain," but we're strong enough to get over everything life throws at us and we will only be stronger for it.

"Sometimes you’re gonna have to lose / doesn't matter how fast I get there" reminds me to trust myself and to not obsess over failures. Sorry if that was cheesy, but anybody who doesn't get emotional listening to this song is clearly not listening to the lyrics or is just not an original Hannah Montana fan.

Sera Pensoy’s Take:

I love The Climb, partially because of young Miley and my strong attachment to Hannah Montana, but mainly for its message of resilience. The first verse touches upon the idea of self-doubt, and it is so wise; I like how she does not acknowledge whether the situation is objectively difficult to deal with, because that isn’t the point, is it? The person in our way is always us.

This song is genuinely helpful to listen to because she is surrendering to the relentless journey. Things don’t always get better quickly, and sometimes the end is not at all in sight. But you just have to do whatever you can to cope, and to keep going, since that is the only way you’ll succeed… and once you’ve made it, you’ll realize that the achievement is not where you are now; it was the journey!

Sera Pensoy: Put Your Records On: Corinne Bailey Rae

My song of choice to get me through tough times is Put Your Records On by Corinne Bailey Rae. It never fails to make me feel happy with its relaxed beat, happy melody and reassuring lyrics. First of all, it is so cute! “Three little birds sat on my window, and they told me I don’t need to worry”: what a glorious image. While that lyric is quite light-hearted, there are other phrases which ring very true: “the more things seem to change, the more they stay the same.”

You can feel so overwhelmed with the speed of life sometimes, but when you calm down and think about it, nothing is actually so bad… it’s not that deep! That is the essence of why this song is so great. Just let your hair down, relax, everything will fall into place and you don’t need to worry about it!

Su’s Take:

The song reminded me of my plans for the past summer break. But instead of reminding me all the ominous news, cancellations, and the stuck at home situation, it made me think about my plans, what I wished to do, what I dreamed about with my friends. Besides, while listening to the "girl, put your records on, tell me your favorite song" part of the song I felt especially connected to Sera, as if she sent me her favorite song and wants me to do the same.

Alongside the soothing melody of the song—which, in fact, directly places a smile on your face—the lyrics were like those of a Disney movie, pulling you towards a "cinnamon" scent and the image of a chorus of laughter shared with your most sincere ones.

Su Karaça: Oft Gefragt - AnnenMayKantereit

The song is about someone whom we call home. Up until my twenties, I had to leave more than five cities and my family for a high school in a different city, and eventually, the country I am a native to to attend a university in another continent. Slowly, I realized that I was leaving not only the cities but also the people behind. The more I left, the more disconnected I felt. Yet, at the end, the smooth realization of "people whom I call home" hit me. They were not right beside me, but I always knew that spiritually they are as close to me as an actual physical home. We possessed unconditional love and trust, which is what makes a house a home.

The song is in German (I apologize for the more work if you are lyrics person. Umm... I am from Europe :)) Even though the lyrics are not complicated, with the music and all the other emotions it evokes, this song is always a refuge for me when I need to remember the people who shaped my life.

Andrew’s Take:

It’s funny hearing a song like this and not recognizing any of the words, yet still feeling like you understand what’s going on. “Oft Gefragt” is melancholic, nostalgic and yet still kind of optimistic. When listening to it, I’m reminded that I’ve kind of left my loved ones behind, and though we’re not physically next to each other, we’re still connected.

It’s odd—listening to it, I’m reminded of the people back in Canada whom I call home, and yet I also think of the friends I’ve made here in Chicago who have also become part of my life. It’s a bittersweet bop, knowing that in due time I may need to pack up again. But at the same time, it’s a kind reminder that the connections I make wherever I am may last beyond the bounds of any geography—an apt metaphor for living in transit, I suppose.

Denise Ruiz: DESPERADO - ALI

Denise: After a really somber year with so much senseless suffering, a song so unabashedly energetic and, well, fun, is a breath of fresh air. The joy and pure energy that radiates from this song is infectious and always manages to lift my mood. Hearing this song even inspired one of my Spotify playlists for music that manages to uplift me after a hard day.

“Desperado” is fundamentally a song about freedom both within the contents of the lyrics and how fearlessly ALI experiments with sound. Desperado is a unique, and almost effortless, mix of J-Pop and Samba. ALI sweeps you off your feet while stimulatingly taking you on a journey where right as you collect your bearings the song switches it up on you again and again.

Lead vocalist Leo Imamura breathlessly switches through three languages (Japanese, Spanish, and English) throughout the song until there are moments in which you can’t even tell which language they are singing in. Its chaos and confusion but it’s beautiful. And maybe the lyrics don’t matter as much as how the song makes you feel at the end of the day.

WENWEN’s Take:

I must say, I was not expecting this incredible mix of languages and genres, and I loved every bit of it. The track started off with a lo-fi vibed muted piano riff and a soothing rap verse, reminding me of the soothing comfort that came with Epik High’s Sleepless In. Then, I was pleasantly surprised by the drums kicking in and the song picking up into a upbeat bop of a jam.

I loved how instruments were joining in and fading out throughout the track. It kind of reminded me of the days when I would hang out with my friends at their jazz practice sessions. There is this repetitive melody that loops throughout the song, like its saying, “no surprises, we’re just here to have fun.” And I sure had fun throughout the entire track. This song feels like its bringing the party to my room, a feeling that’s been lost to me since the Before Times.

WenWen: Sis Puella Magica OP - Yuki Kajiura

First, I would like to apologize for the very 2010s anime art that comes with the thumbnail. If you have seen this show, the moment the choir starts your mind would be filled with the imagery of the grey skies and purple aftermath of the Walpurgis Night. The agony that came with sacrifice and loss, and finally, the pink glimmer of hope that Madoka held onto until the very end, every single time.

These days a lot of us have been going back to nostalgic obsessions for some sense of comfort. This track, from the OST of Puella Magi Madoka Magica, walks along the lines of that. It dances along a comforting sadness that is familiar and expected, which is much more soothing than the unexpected and surprising kinds of sadness that life keeps throwing at you.

I like how this song kind of wraps around you the entire time, like you're encased in it, but you don’t have to give it your attention the entire time. I like to do my homework to this track, along with other OSTs from the series. I am not really sure how this track would sound to someone who is unfamiliar to the show, but I hope it is an interesting experience nonetheless. I hope you enjoy!

Andrew’s Take:

It’s kind of funny, for as much as I talk about anime and manga on his blog, I’ve never been super invested in any of their soundtracks (except for the Yuri on Ice! soundtrack, it slaps). That being said, I think I resonate with WenWen’s words. A lot of us have been returning to nostalgic things that once comforted when we were younger, and for that I respond really well to this song. Admittedly, WenWen is right, it’s tough to enjoy the song the same way having not seen Madoka, but that being said, it’s kind of cool to try and glean what a show might be like from their opening/main theme, and the sequence is both mysterious and quite epic, so perhaps I will get into it after I wrap up Yuri on Ice! for the five thousandth time.

Esha Deokar: I Smile - Kirk Franklin

When I first heard of Kirk Franklin, it was off of Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam.” The intersection of rap and gospel music was something I had never heard of before, and as someone who doesn’t particularly subscribe to a specific religion, it was much more appealing than I had imagined. I took to Franklin’s tenth studio album, Hello Fear, as a starting point to that new world of music.

“I Smile” took me by surprise –– much of the music I had listened to when I was sad or emotion was very minimal. Not too many drums, maybe some light synth, but nothing excessive in the auditory sense. On the other hand, “I Smile” embodies maximalism; the choir explodes in the first few seconds of the song into a dynamic and energetic rhythm. Its superlative qualities definitely inspire something in me; it has the power to pull me out of my own head in times of need.

Whether it's my mood or the situation at hand, when I need something to change, Franklin’s vivacious choir, undercut with remnants of R&B and funk, fits the bill.

Henry’s Take:

At first, the soulful gospel-like style of "I Smile" felt like it was not for me. I don't mix religion with music, and generally, gospel is just not something I enjoy listening to. But I must say, the song is both catchy and uplifting. The repetition of the message that even though your day may be bad, you can still find the beauty in it and smile is the quintessence of what a song about going through the hardest of moments would sound like.

I may not believe that something from above can give me the power to face the day and smile through the pain, but I understand that faith in something and faith in somebody's own ability to thrive in the most distressing moments is in itself a powerful thing.

Alessandra Tufiño: Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Elton John

I picked the song “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” by Elton John; I love this song because it has a great sound, and very powerful lyrics that have helped me get through hard times. When I first heard this song, I was going through a hard time in my first quarter of my first year. I was having a hard time finding myself and knowing what I wanted and I overall just felt overwhelmed and generally bad.

This song made me cry the first time I heard it, because it kind of felt like a reminder that there is more to life than what I do in school and that isn’t my only path in life. So now whenever I listen to that song during a tough time, I remember when I first listened to it, and that helps.

Bonnie’s Take:

All Elton John songs are feel-good songs for me. Maybe it’s the piano. Maybe it’s just Elton John as a person. I think this is one of the very few songs that makes me feel like a main character. It doesn’t have the playful, carefree energy that “Be-Be-Be-Bennie and the Jets” does, but it’s so much more dramatic. It reminds me of those movie endings where the couple doesn’t end up together, but you know it was the right ending for them both.

The song plays as the character walks home, (~goodbye yellow brick road~), then cue split screen of the two, both alone and soulfully looking out the window. You feel sad that they didn’t work out, but are happy that they put themselves first. It was a tough decision, but it was the right one. Me, I’m the main character.

Bonnie Hao: Make it Go Right - Childish Gambino

How can a song that starts with “Where is this song in my Blackberry?” not make you feel nostalgic? Though the audio quality sounds like a 10 x 10 pixel image, this song is the only reason I still use Datpiff (a goated but outdated streaming platform that makes me feel like I’m 12 again). This song got me into Kilo Kish, her voice is cotton candy lipstick, so soft and lovely.

2012-13 was also a particularly formative period for me. I was obsessed with Community, so hearing Bino say he’s gonna hold “my” hand in little Tokyo was like warm fuzz. There’s just no way for me to describe how happy this song makes me feel! Give it a listen and I hope you’ll feel the same (:

Alessandra’s Take:

This song made me nostalgic for a simpler time, probably because it kind of gave me an image of high school, and the beat of the song also felt like something I would have heard a few years ago. I could definitely see this song being listened to when someone is going through a hard time, since it sounds nice and kind of reminds you of simpler times, so I could definitely see myself listening to it trying to remind myself of that.

Featured image via Andrew Chang

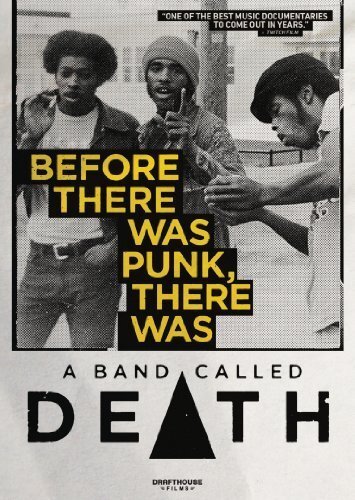

Before There Was Punk, There Was Death

Punk subculture is a coalescence of countless radical aesthetics and convictions. Irrepressibility. A do-it-yourself spirit. Anti-establishment and anti-authoritarian mindsets. Rebellious attire.

Notorious whiteness.

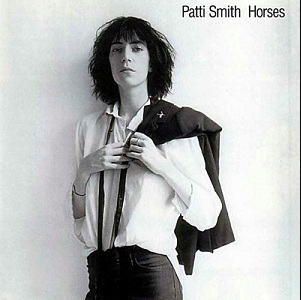

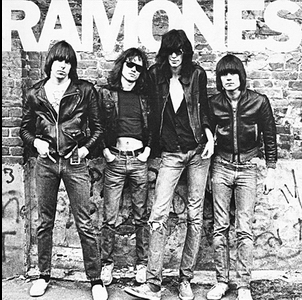

With the rise of bands and artists from the likes of the Ramones, Patti Smith, and the Sex Pistols in the mid-70’s, three black brothers from Detroit, unbeknownst to the rest of the world, had already laid out the foundation.

The story of the brothers was recalled in a 2012 documentary film titled A Band Called Death, directed by Mark Christopher Covino and Jeff Howlett, and follows two of the brothers as they tell the tale of Death and its new found glory decades after their disbandment.

The film begins, after a compilation of confessions from musicians like Kid Rock and Questlove, by giving us tracking shots of worn down houses, caved-in rooftops, and dilapidated arches that read

MO OR CITY IN U T R L PARK

in Detroit, Michigan. “Welcome to my neighborhood,” Bobby Hackney Sr. boasts, “2240 Lillibridge. This is where Death was born.”

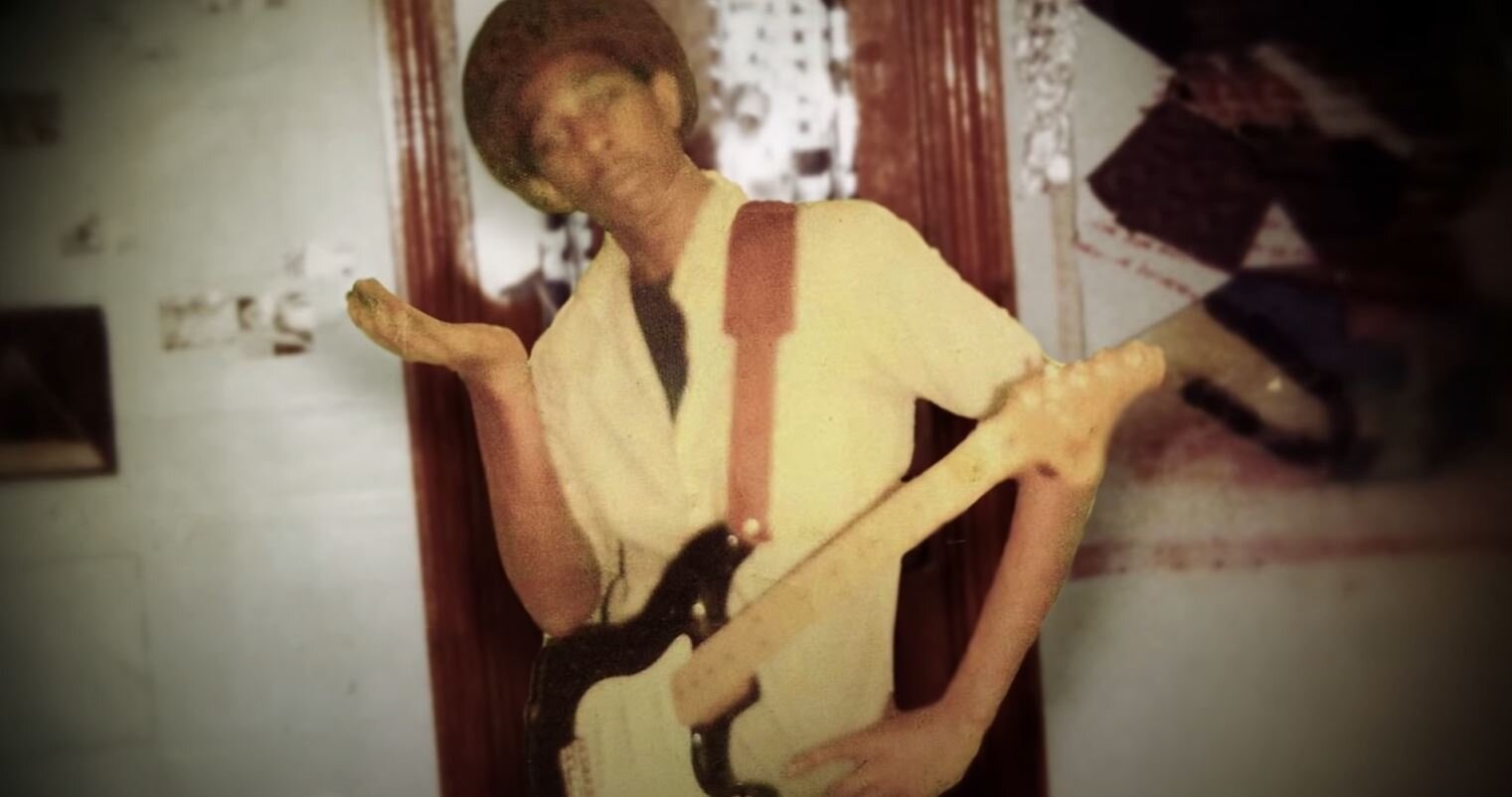

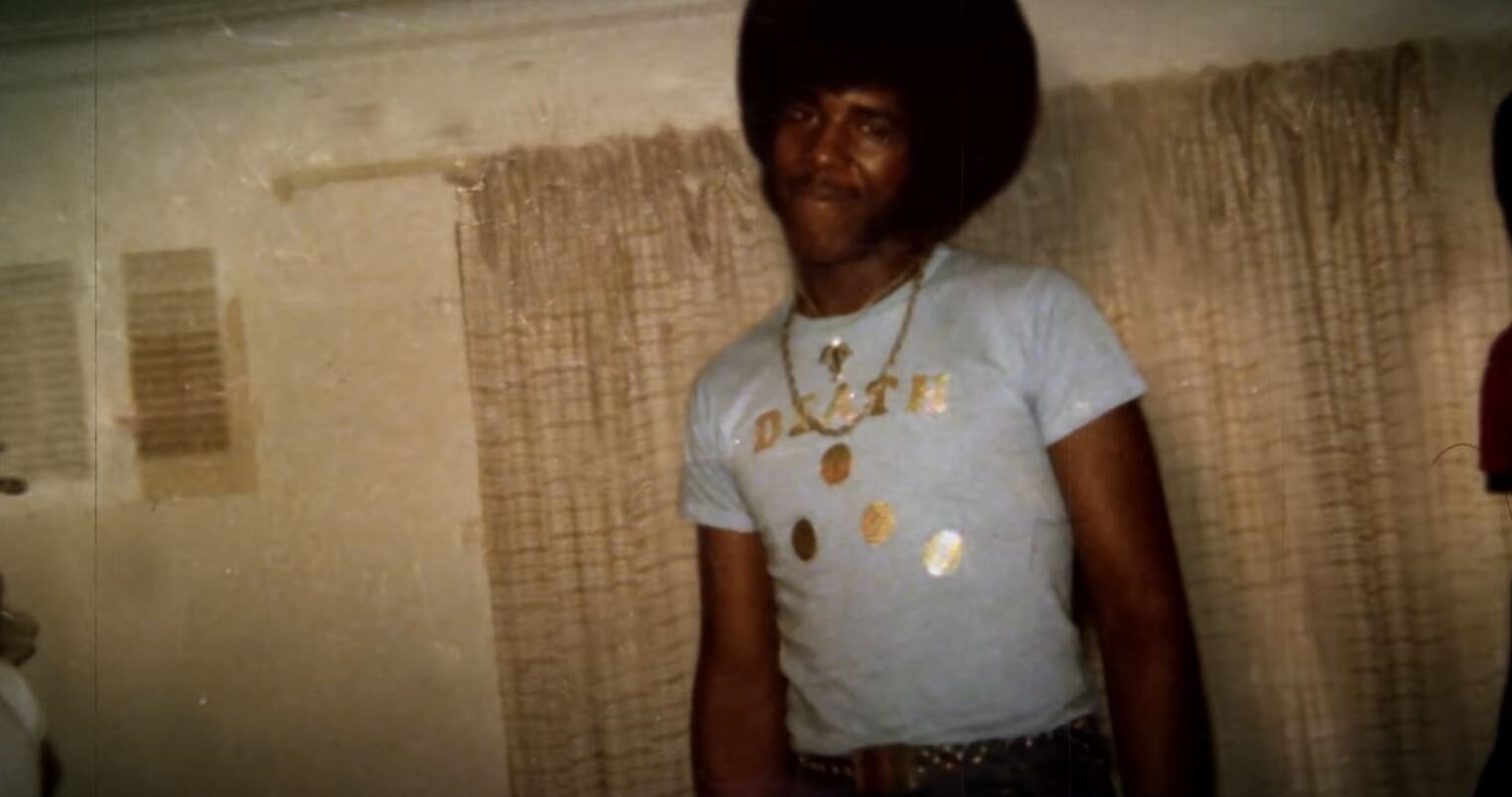

The band was composed of Bobby Hackney Sr. on vocals and bass, Dannis Hackney on drums, and David Hackney as guitarist, songwriter, and leader.

The Death brothers grew up during Motown time in Detroit, preacher’s sons with spirituality rooted deep within them. It’s when their father sat them down to watch The Beatles play that they knew music is what they wanted to do. It was David that rallied them together to form the band. The brothers, unsure whether they wanted to be a rock or a funk band, were first called Rock Fire Funk Express. When David went down one day to see The Who, he knew rock and roll was the music they had to play. And when Dennis saw Alice Cooper, all bets were off.

The Death Triangle

After the death of their father, in Spring of 1974 David came up with the name that changed it all: Death. Their name would always have shock value, because “death is real,” David claimed. The goal was to put a positive spin on death, the ultimate trip. The circles on the band’s logo, the Death triangle, represent the three elements of life: the spiritual, the mental, the physical. The latter circle is the guiding spirit of the universe. It’s God, really.

Dannis and Bobby still ooze musician cool decades later, the brothers bringing the crew throughout their home while pointing out corners of memories and the ghosts of their instruments. This is where Dannis’ drums would be. This is where David would stand.

The name was a roadblock, but wouldn’t change under any circumstances. “If we give him the title of our band,” David said on record producer Clive Davis, “we might as well give him everything else.”

And what’s more punk than resistance? Than persistent blackness?

They don't care who they step on

As long as they get along

Politicians in my eyes

They could care less about you

They could care less about me

As long as they are to end

The place that they want to be

Politicians in My Eyes (1974/2009)

It’s in this discomfort that Death crafted itself as a band ahead of its time, proto-punk among an age of angsty whiteness.

But is it really all in the name? I don’t bite.

Black folks time after time are forced to deal with their invisibility and hypervisibility in popular culture. In the 70’s, the association with black musicians to the Motown sound, especially in its birthplace of Detroit, left artists like the Hackney brothers in the dust of a seemingly whitewashed sound: a sound that they pioneered.

“We were ridiculed because at the time everybody in our community was listening to the Philadelphia sound, Earth, Wind & Fire, the Isley Brothers,” Bobby said to Red Bull Music Academy, “People thought we were doing some weird stuff. We were pretty aggressive about playing rock ’n’ roll because there were so many voices around us trying to get us to abandon it.”

Their inability to get radio play caused them to sell most of their equipment, and in 1977 Death disbanded. Dannis and Bobby closed the book on that chapter in their lives and formed reggae band Lambsbread in the 80’s. Before David’s eventual death in 2000, he told his brothers, “The world’s gonna come looking for the Death stuff.” And he was right.

In the early 2000’s the resurrection began. The newfound discovery of Death was an anagmalation of things: Bobby Hackney’s sons’ interest in the punk rock scene, the influence of musician Don “Das” Schwenk, and the mysterious ways in which the universe can only discover a band of visionaries lying in wait decades later. Schwenk, a longtime friend of the Hackneys, was commissioned to create the album art for what would have been the Politicians In My Eyes LP back in the day: unable to pay him, the brothers gave him copies of the LP instead. Years later after Death’s demise, Schwenk began to hand them out to collectors. “It’s never too late,” he said.

The track list to Death’s original master tape from the 70’s

As the record began to circulate among collectors circles, niche popularity grew. It made its way to Chunklet magazine and eventually began to spin at underground rock ‘n roll parties. It’s how Julian Hackney, son of Bobby, discovered that his father and two uncles were punk before punk was punk—since the brothers never felt the need to tell the kids about all the rejection they went through as rock stars. After a friend of Julian recommended him to listen to the band Death, his father’s voice on the record was unmistakable. The discovery led to Bobby’s sons forming their own band, Rough Francis, to cover Death’s music.

And there is something quite beautiful about that. About the legacy of music passed down almost hereditarily, though unconsciously. It’s Bobby’s sons who made it their mission to get the music out, to let the world know that their father and uncles were the predecessors of what punk became. In 2009, Death was able to officially release their 1970s demos as the studio album …For the Whole World to See: it was named decades before by their late brother, David.

In the opening of the film, the camera follows Dannis and Bobby haphazardly, panning back and forth between their conversation with old neighborhood friends. When Bobby tells one of them, “They’re telling the story about death,” the woman shrugs, “I’m still here!”

Sounds familiar. Sounds like a legacy. Sounds immortal.

Bobby and Dannis Hackney showing off their official 2009 studio album, …For the Whole World to See

A Band Called Death (2012) can be streamed on Prime Video, or Youtube.com

…For the Whole World to See can be found directly on Spotify, Apple Music, and other streaming platforms

Unlinked pictures, including the featured image, were stills taken directly from A Band Called Death (2012)

J Dilla, "Donuts", and the Legacy of Copywriting

It’s Time for You to Get into Kylie Minogue

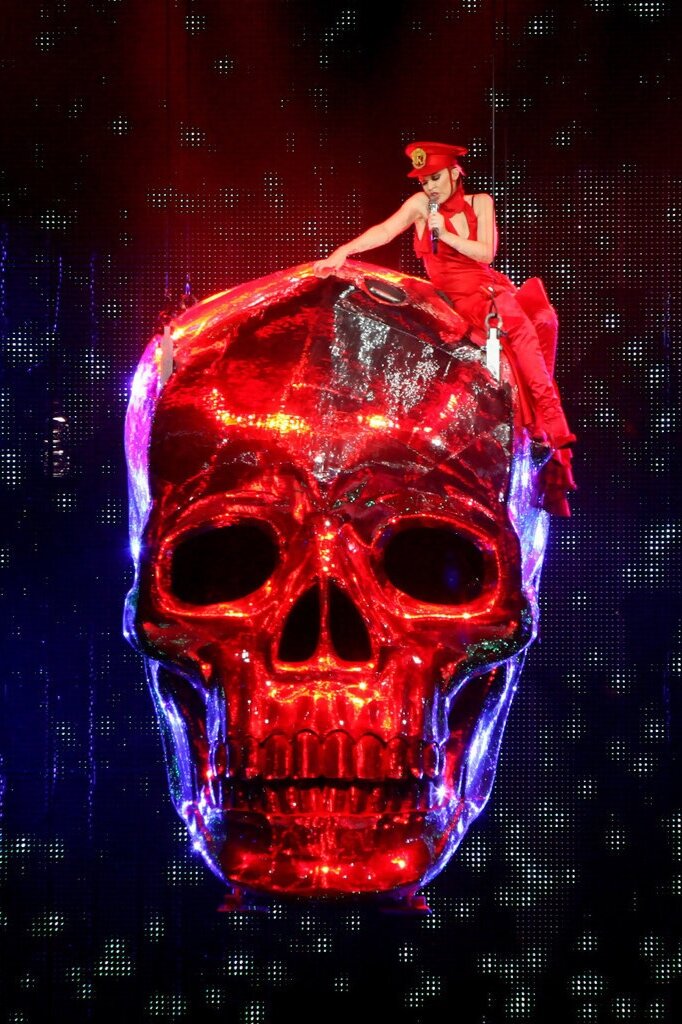

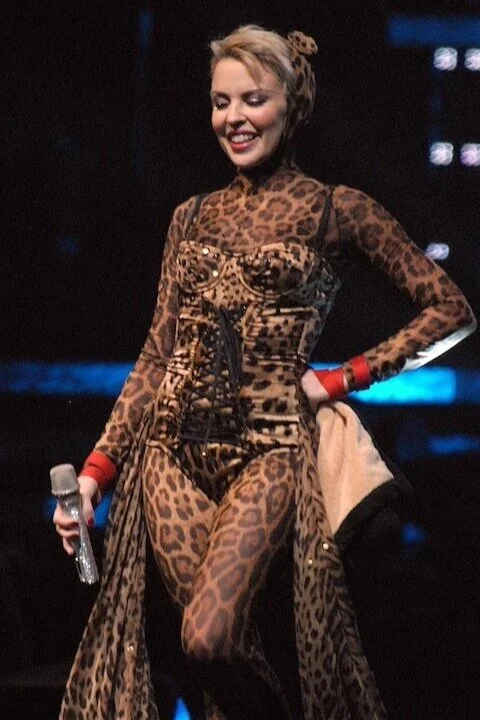

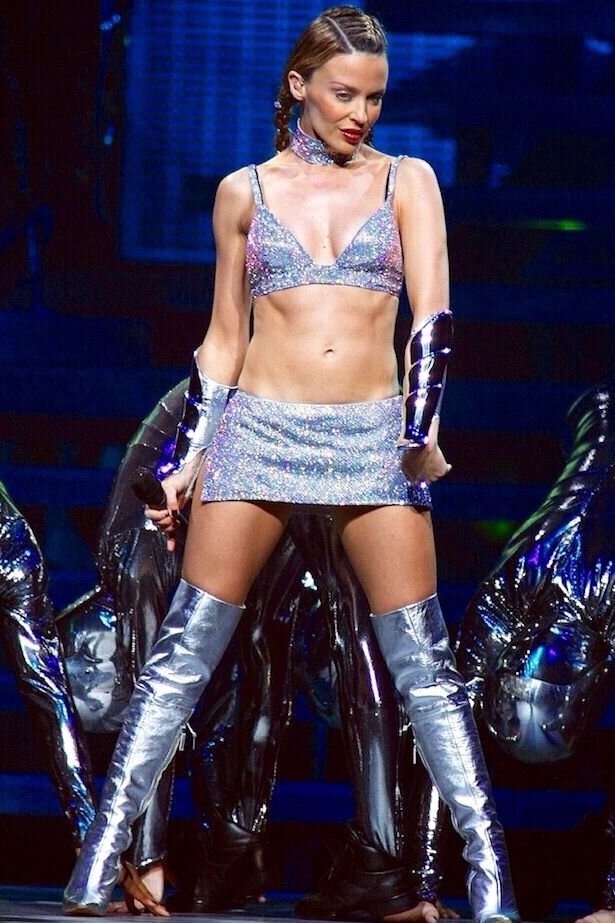

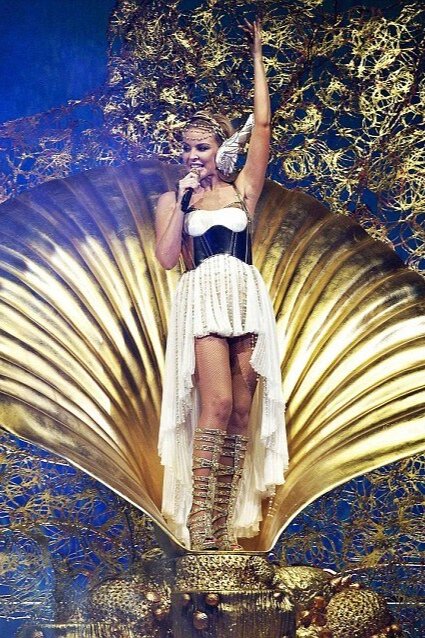

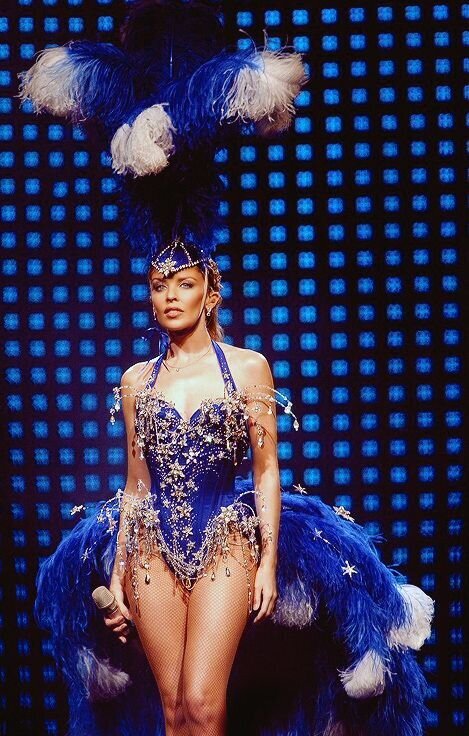

Last November, Australian queen of pop Kylie Minogue flexed her penchant for dance-pop excellence yet again with her latest album Disco and the stunning virtual concert, Infinite Disco, that accompanied it. Though she’s an absolute superstar internationally (to the tune of 70+ million records sold and #1 albums on the UK charts across five different decades—the only artist to ever do so), Minogue never quite lit the spark to engulf the United States with Kylie Fever. She had a brief moment in 2001 with the ubiquitous hit “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head”, but at a time when an absurd amount of would-be Britneys (Mandy Moore, Willa Ford, and Jessica Simpson, to name a few) were scrambling to reach pop princessdom, Minogue’s talents were honestly better served elsewhere. It was our loss!

Her 30+ year career is marked by a series of reinventions and an uncanny ability to adapt to the musical landscape. Her songs range from Bond-esque epics (“Confide in Me”) to rock (“Some Kind of Bliss”), but she’s most beloved for her bubblegum pop staples, leaning into the shimmery disco conventions rebuked by many in favor of pop with “grit” and “substance.” She’s a pleasant anomaly in an industry that loves to throw out its pop princesses before they’re old enough for queendom, as she continues to conquer the world with high energy, high concept tours into her fifties. A verifiable fashion icon, master of camp, and quintessential showgirl, a Kylie Minogue show always features immaculate styling and production.

As 2020 saw the surge of nu-disco reaching a mainstream fever pitch, Kylie Minogue descended from her place in pop’s glittery firmament back to show the young girls how to do it. Over her time in pandemic-induced lockdown, she learned Logic Pro and engineered her own vocals for Disco. The Infinite Disco concert featured Minogue unironically wearing a lamé jumpsuit among a torrent of strobe lights, asking viewers for nothing more than to get lost in the glitter and dance along. She topped off the year with a guest appearance at Dua Lipa’s Studio 2054 concert, who in turn appeared on a remix of Minogue’s “Real Groove.”

Here’s a brief primer on Kylie Minogue’s historical pop excellence and the Disco tracks that’ll keep you hooked:

The Classic: In Your Eyes (2001)

To me, nothing says Kylie Minogue like In Your Eyes. It’s got everything: mystique, danceability, a ridiculously infectious melody. The music video is a gorgeous rush of stimuli. Essential viewing.

The Disco Response: Miss A Thing

My personal favorite track from Disco dips into the early 2000s dance pop groove and injects a heaping dose of hypnotic ‘70s ecstasy: breathy vocals, elegant strings, and a calculatedly perfect rhythm follow. If you liked Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia, these are the tracks for you.

The Classic: Your Disco Needs You (2000)

General Kylie leads an army for the defense of truth, justice, and the hedonistic way with this mind-blower of a song, campy to the max. A massive orchestral-backed chorus and slinky verses encourage us all to leave behind trivial things like Scrabble (?), vanity, and war in favor of a good time at your neighborhood disco. Very Village People meets Boney M., its a bit off the beaten path for straight laced pop fans but worth a try for the funkier among you.

The Disco Response: Magic

Album opener Magic is a dreamy, optimistic manifesto complete with requisite horns and staccato rhythms for a sparkle-filled firework of a song. It’s quintessential nu-disco, hitting every beat with just the right level of pizzaz.

The Classic: Closer (2010)

A dark, throbbing keyboard evokes cosmic ABBA tunes like Money, Money, Money or Lay All Your Love On Me. Very mysterious, very rich, very classical, and very wonderfully weird with its faux-harpsichord sound. It’s kind of what I think The DaVinci Code would be if it was a song.

The Disco Response: Where Does The DJ Go?

A similar, if more danceable, kind of drama laces this song as Minogue leans back into the ‘80s for some Niles Rodgers-inspired arrangements (the instrumentals backing the verses give off strong “Le Freak” vibes). The chorus directly fixes the song in the legacy of glitter-soaked ‘80s disco with its urgency and gossamer sheen. The intro is a classic Donna Summer-esque fake-out (hello, “No More Tears”), and the chorus quotes disco epic “I Will Survive”. Get it yet?

The Classic: Spinning Around (2000)

One of Minogue’s many career comebacks, this was her first chart-topper since 1994’s “Confide In Me”, and she could not have been more accurate when she exclaimed “I’m not the same!” A funky bass and vocoder-laden chorus kick off her foray into 21st century disco-pop.

The Disco Response: Last Chance

From the elegant strings to the thudding bass line, Last Chance is disco meets trance in a similar marriage of pop’s foundations and pop futurism.

The Classic: In My Arms (2007)

One of Kylie’s most electro pop songs, this song is a very characteristically late ‘00s synth-laced bubblegum romp, with a syrupy sweet chorus that radiates nothing but sunshine (see also: “Love At First Sight”).

The Disco Response: Dance Floor Darling

Half “driving with the top down in LA,” half 2 a.m. club energy, 100% joy. In Kylie World, there’s no problem that can’t be solved by a dance floor.

The Classic: Red Blooded Woman (2003)

Minogue is a chameleonic popstar of the highest caliber, never content to rest on her sonic laurels. After her techno-pop smash hit album, Fever (2001), she veered into a wider breadth of influences. Red Blooded Woman is a showcase of thumping Europop and hip-pop-esque rhythms, topping off the endlessly dramatic production with a sprinkle of Psycho-esque string trills backing the chorus.

The Disco Response: Real Groove

Kylie’s voice blasts off into outer space with a cool, vocoder’ed tune that is just as much a product of post-disco house as Kool & The Gang, a stellar showcase of her timeless ambiguity.

Featured image via

Girls Eat Sun: Hope Tala Shines On Latest EP

Hope Tala’s latest EP delivers exactly what its cover art promises: a wonderland of coffeehouse surrealism.

A finch dons a nightdress and clutches a teddy bear in its beak. Two cherries dangle like earrings, smiling lovingly at each other. Droplets of sun drip from Tala’s mouth to chin.

It shouldn’t make sense. But this otherworldly carnival finds grounding in the lyrical prowess of London’s darling songstress. Over the warm tones of her acoustic guitar, Tala weaves together a series of corporeal metaphors, equal parts poetic and relatable.

Image via

Newcomer to the R&B world, Tala first made waves with debut EP Starry Aches in 2018. Sultry tracks like “Blue” garnered praise from major music outlets Clash and Complex. In 2019, Rolling Stone declared her follow-up track “Lovestained,” “the Song of the Summer Morning.” By the release of her sophomore EP, Sensitive Soul, it was clear the neo-soul singer had accomplished the near-impossible: turning heads in a genre plagued by monotony.

While Tala is no stranger to the limelight, Girls Eat Sun represents a breakthrough moment of new proportions. With a feature from platinum-certified Aminé and an outpouring of love from top media platforms, Tala’s latest release positions her at the precipice of mainstream stardom.

“The title is a paraphrase of ‘if you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen’ – as the girl eating the sun, I’m daring and fearless.”

“At the core of Girl Eats Sun,” Tala writes, “ is an assertion of confidence and boldness. The title is a paraphrase of ‘if you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen’ – as the girl eating the sun, I’m daring and fearless. I chose this title because I feel as if the songs and stories on this project are more vivid and inventive than anything I’ve released thus far, and I’ve pushed my sound in different, exciting directions.”

The 6-track set opens with “Mulholland,” a rule-breaking rumination on love at the intersection of LA nightlife. It’s a sleek prelude - soft, sunny, and infinitely clever in its hook capacity. Tala reels in listeners with her lyrical dissonance. Tender acoustics confuse far darker melodies. “I etch myself into the sky,” Tala croons over upbeat syncopations. “[Drugs] wouldn't leave me lost like you do.”

“Mulholland” fades seamlessly into the Spanish guitar riffs of “Cherries,” the EP’s standout single. A lyrical masterpiece, “Cherries” is a personal triumph for the recent Literature graduate, who’s poeticism bleeds lovingly into her music. The opening verse belongs in a literary magazine:

“The cherries in your mouth spill stars

Scarlet venom to keep in jam jars

We all build worlds with joined up scars

But your constellation has stained my guitar

And the french in your mouth breaks ribs

Makes heads go light and hands lose their grip

Pulling teeth behind a bottom lip

To look for cherry stones and rotting apple pips”

In an interview with Refinery29, Tala muses, “I think of 'Cherries' as being about the human body. When I was writing its lyrics — lines like 'The tears I cry' and 'pulling teeth' — I was thinking about how I could use the body and its functions to craft complex metaphors that talk about emotions and feelings.”

Image via

Corporeal metaphors collide with Renaissance imagery in the single’s new music video. Tala poses in a brigandine and clutches her sword while avoiding a FaceTime call from feature artist Aminé. He offers a refreshing counterpoint to Tala’s airy vocals, rattling off lyrics as cocky and playful as the track’s plucky tempo.

“All My Girls Like to Fight” serves as the EP’s middle-point and, perhaps, thesis. Previously released in September, this ode to female empowerment immediately caught the streaming world’s attention. In an interview with Wonderland Magazine, Tala states,“ I wanted to create a visually rich tale steeped in drama and intrigue to match the suspenseful Spanish guitar chords we started with in the studio...I wanted to portray women as having strength and agency in their narrative.” “I lick their hands clean of bark and bite,” Tala sings. Fitting of a project dedicated to women devouring the sun itself.

Interlude “Drugstore” wanes into low-fi love ballad “Crazy.” In one of the EP’s most tender moments, Tala waxes poetic about an oncoming crush; “Plant rosebuds on my cheek, I'll blush like rosé wine. And if you water them enough, I promise we'll be fine.”

The EP culminates in a gentle redux of its opening track. “Easy to Love” is a Sunday morning gone wrong, the inevitable conclusion to Tala’s surrealist wonderland. Darkness looms beneath sunny acoustics. “I can see your heart beneath your ribcage,” Tala opens. “You should save it for me.” Minimalist in its production, “Easy to Love” showcases Tala’s breathy tones like no other track in the set. Viscerally sweet, the outro progresses like a fever dream, softly fading into the antiworld from which this project emerged.

Girls Eat Sun was released on all major streaming platforms on October 30th. New music is (hopefully) forthcoming.

Feature image via.

Artist Spotlight: Overcoats

When asked:

“Siblings or dating?” Hana Elion and JJ Mitchell, the singer-songwriters who are Overcoats, answer: “yes.”

“What are you guys listening to right now”: “the voices inside our heads.”

“Why did you shave your heads”: “so we could finally get boyfriends.”

Clever, funny, and incredibly talented, the duo met on their first day of college at Wesleyan University and have been making music together ever since. Their work doesn’t fit comfortably in one genre—it’s a combination of electronic pop and folky harmonies that sometimes approach bluegrass. But genre (or lack thereof) isn’t what attracts me to Overcoats—it’s their genuine emotional vulnerability.

Lyrics matter to me. If I don’t feel connected to the words of a song, I rarely keep listening to it. Maybe this doesn’t mean much in the grand scheme of things, since we all relate to different things in music, but I have never pressed skip on an Overcoats song. The duo addresses issues like sexism in the music industry, depression, anxiety, politics, and they consciously include lines that show how often two opposing things can be true at the same time. Their words are simple, honest, and make me feel.

In March 2020, Overcoats released The Fight, an album they describe as “a ten-song battle-cry.” It follows their critically acclaimed debut album, YOUNG, released in 2017, and their vision “is not about picking up arms, but rather about picking oneself up.” With driving rhythms like Fire & Fury and Apathetic Boys next to gentler tracks like Drift and New Shoes, Elion and Mitchell have created a record that I catch myself listening to every way I can—on shuffle, adding individual songs to my favorite playlists, or all the way through in order (as I’m doing right now).

Mitchell and Elian’s videos are just as thoughtful, creative, and (there’s no other word for it) cool as the songs themselves. In one of my favorites, The Fool, Mitchell and Elian shave each other’s heads. They were inspired by women in history who cut off all their hair as a political and social statement (think Sinead O’Connor and Grace Jones), as a way to push back against the way they were being pressured to present.

For the artists, the name Overcoats acts “like a suit of armor. Something…genderless, ambiguous,” and shaving their heads reaffirmed that ethos of rejecting gender norms and defining themselves however they choose. It’s powerful, beautiful, and if my hair weren’t already buzzed it would make me want to pull out the trimmers and unweight my scalp. There’s something about the way that video, in particular, is shot that’s just different—I can’t put into words. Go watch. (and take a peak at Fire & Fury while you’re at it)

If this has made you at all curious about Overcoats, they’ll be playing a livestreamed concert on November 19. Get tickets ($12 plus fees, around $15 total) here. And yes, I did listen to all of both of their albums while writing this post. You should, too.

Thumbnail image via Instagram, inline images all from Instagram

Music to Reflect and Move Forward

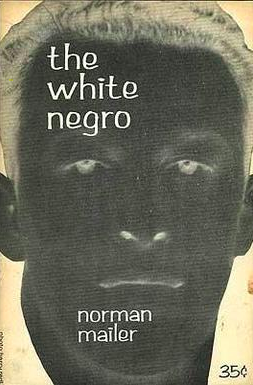

Blackness and Authenticity in Punk

It’s incredibly telling that rock critic and historian Greil Marcus was able to pronounce what punk rock was in 1979 – just two years after Nevermind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols was released, the only album by the band he calls the “formal (though not historical) conclusion” of punk. Punk was a brief flash of brilliance, an explosion whose shrapnel we are still feeling today as the genres that splintered off: post-punk, hardcore, new wave, noise rock, pop-punk, whatever term the editors of No Depression finally settled on, and ultimately all of “alternative” rock. One way or another, punk is the year zero for all rock music that came after; its effects are hard to overstate, and go far beyond the music.

Marcus argues the Sex Pistols took punk’s first-wave to a vitriolic conclusion by redefining it in their image, away from the avant-garde punks of New York. Self-appointed dean of rock critics Robert Chistgau describes the work of “avant-punk” as:

harness[ing] late industrial capitalism in a love-hate relationship whose difficulties are acknowledged, and sometimes disarmed, by means of ironic aesthetic strategies: formal rigidity, role-playing, humor. In fact, ironies will pervade and, in a way, define this project: the lock-step drumming will make liberation compulsive, pain-threshold feedback will stimulate the body while it deadens the ears…

The Pistols dropped the “avant-” and with it the irony and self-conscious artistry of Patti Smith, Tom Verlaine, Lou Reed, and other seminal avant-punks. In its place they put – or at least Rotten and Vicious put – unadulterated, ugly nihilism. This is why Marcus places Sex Pistols at the formal conclusion of punk: they were committed to the destruction of everything, including (paradoxically) rock itself. Unlike the Clash, who were careful to be on the right side politically, the politics of the Pistols was pure negation in its most gleefully manic form. This is what makes listening to Nevermind the Bollocks exhilarating, to this day: the guitars assault the senses while the drums clamor away oppressively, and Rotten – what hasn’t been said about him already? His snarls, his rolled-R’s, half-sung half-growled, that devious cackle; he’s the most convincingly nasty singer rock’s ever seen. When Rotten says he is the Antichrist, you almost believe him.

Rotten’s lyrics are loathing-filled tirades, the product of unfocused dissatisfaction channeled into hate and aimed at anything in sight. Listening to the Pistols is less an experience of having your dissatisfactions reflected back to you than magnified, made metaphysical in scope, and as Christgau writes, aimed at – for the time in rock – those in power. He is a lightning rod for the inchoate rage and dissatisfaction in the listener. He gives the intoxicating feeling of having the freedom to take things too far, of hearing your worst impulses acted out, of glimpsing something beyond the claustrophobia of ordinary life, of, as Elvis Costello sang, biting the hand that feeds you. It can be childish, but also often brilliant and beautiful. The Pistols showed the pure joy of hate.