Post-Soviet fashion: a catchall term used to describe the trend that takes inspiration from Cold War and Eastern Bloc fashion by incorporating Cyrillic lettering, vintage styles, textures, and aesthetics.

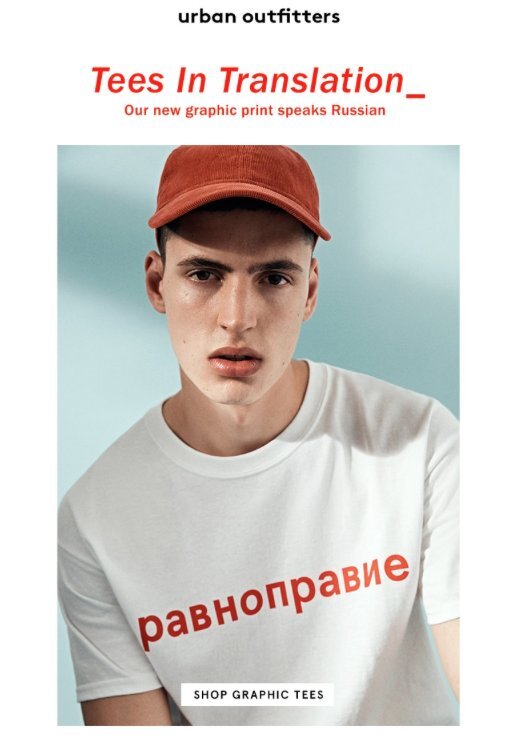

Post-Soviet fashion experienced an uptick in its usage, specifically in alternative or indie clothing brands, in the past 3 or so years. Most famously (or infamously, depends on how you look at it), a couple years ago, Urban Outfitters released a t-shirt with the Russian word for “equality” on it. While their translation was correct, there are many designers that unfortunately did not have the foresight to check their Google Translator app with a native speaker, resulting in mass produced grammatically incorrect sweatshirts.

My question is where did this trend come from? And more specifically, is it ethically sound to retroactively uplift a sense of style for the general consumer that is associated with so much historically?

In answer to the first question, I have several theories (Disclaimer: I am by no means an expert, this is simply something I took interest in for a hot second). Two of the theories are a little more critical of the origins of post-Soviet fashion, the last is a more positive understanding of the fashion movement. More likely than not, it is some combination of all three.

One way to understand where this came from is by recognizing that Western fashion has always had a problematic obsession with “exotic” fashion. What started out as blatant appropriation of East Asian, African, and Native American cultures is now unacceptable and has thankfully gone out of vogue. Yet even since there has been a notable shift in fashion to reach for the next best thing. As someone from Eastern Europe, I was actually a little surprised and somewhat irritated to see that about 2 or 3 years ago flower embroidery became a really big trend. Now normally, embroidery isn’t particularly associated with any one culture and flower motifs are pretty common everywhere in the world. However, it was striking how much of a resemblance there was between some flowery embroidered tops sold by the likes of Free People and the traditional Eastern European vyshyvanka. For context, a vyshyvanka is a type of traditional shirt worn in Eastern Europe commonly before the Russian Revolution in 1917 and since mostly only appears in traditional celebrations and holidays such as Orthodox Christmas or Ivan Kupala. On surface level, there does not seem to be any malintent in using these designs, yet it is irritating to see companies reproducing these for the average consumer who is buying an iteration of this design in ignorance of its cultural significance.

Images of vyshyvankas via here, here, here. Mass produced reproductions via here, here, and here.

Okay, so Western fashion has had a flirtationship with “adopting” designs from other cultures, but what does this have to do with post-Soviet fashion?

This exoticization of traditional designs was really only the beginning. Post-Soviet fashion is also often associated with color blocking, windbreakers, and tracksuits. More specifically, it emulates 90s gopnik style tracksuits. Arguably, this unholy union of fashion and culture came out of the current unending trend of athleisure. Designers like Gosha Rubchinskiy and Andrei Artyomov, to name a few, certainly contributed to creating a hypebeast vibe around their takes on post-Soviet inspired streetwear. Through large blocky hoodies and FILA-like shoes their Cyrillic branding took over the streets of London, Paris, and New York for at least a season in 2017-2018. Today, while the trend may have died down a little bit, it still raises associations with rising crime and the repercussions of a fallout of an entire structure of life in those of Eastern European descent. For us, looking like a gopnik is not really a desirable or fashionable thing. Instead, it carries the connotation of alcoholism, joblessness, and criminal activity that increased shortly after the official collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The tracksuits carry with them a memory of economic failures rather than something that was considered a distinct style. The iconic three stripes was an outfit of desperation rather than a conscious fashion choice.

Images via here, here, here, and here.

This brings me to my next point, which is slightly more positive. 90s fashion in Post-USSR emerged out of a state of deep social and cultural confusion. For decades, the USSR cultural identity was state created. Upon the fall of the Soviet regime, the social fabric of many countries in the post-Soviet world was simply torn down. Entire nations were struggling to find a sense of identity in the shambles of what was left behind after the regime collapse. This was reflected in fashion choices as well, with the youth of Eastern European cities wearing a strange blend of clothing produced by the extinct Soviet Union and Levi’s.

The resurgence of post-Soviet fashion is something that has been appearing increasingly frequently on the streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg in recent years. For today’s youth, which ironically never saw the era that produced the clothing styles that they choose to wear, wearing Cyrillic sweatshirts or vaguely Soviet vintage clothing is a way of reclaiming some part of that broken national identity that we were born into.

Images via.

Image via.

It also presents an interesting subculture with its own subtle political messages. Many of these shirts are not mass produced, but either individually printed or created in small batches in an almost samizdat-like production. The result is a slew of messages such as Sputnik1985’s “I Will Always Be Against” and Volchok’s famous “No Tsars No Gods” merchandise.

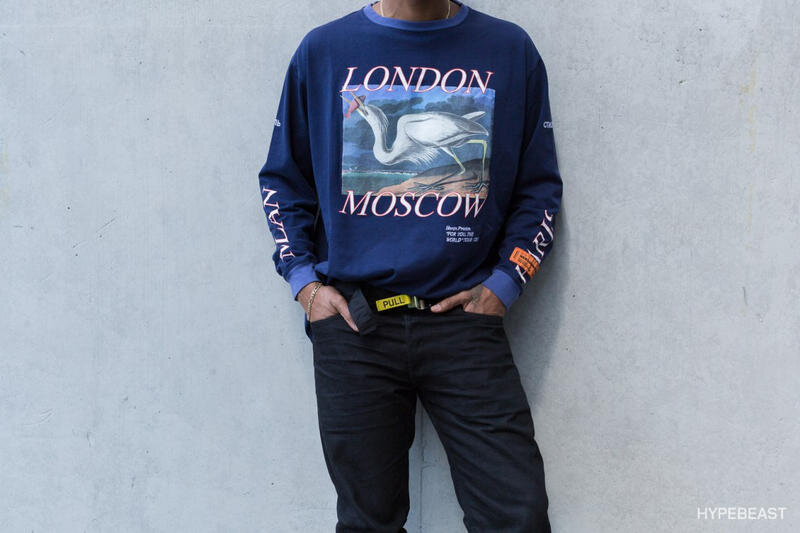

But what happens when these distinctly post-Soviet identities begin cropping up in mainstream Western fashion? Most notably, Heron Preston, a designer in the vein of Off White’s Virgil Abloh, has made an entire brand name on the premise of stamping his goods with the Russian word for style: Стиль. But why “Стиль”? What relevance does it have for his brand or his message? What’s the connection?

Images of Heron Preston collection staples via here, here, and here.

Well, apparently for Preston, none in particular. In a revealing GQ interview the designer said:

“I've used Russia a lot as a theme. It also carried over to be sort of my sub-logo [written as Стиль which translates to "style"]. My partners, New Guards Group, they also rep Off-White, said, "Yo, for your brand, you should launch in Russia because no one is doing that. You have this Russian logo so we should kick off in Moscow and go on a retail tour." I loved it. I normally would have taken a more traditional approach with the launch, and launched in New York. I was just into the idea of being different from a typical launch and it just made sense.”

If this interview revealed anything, it’s that Heron Preston himself seems to have no idea as to why he’s capitalizing on the word Стиль, other than it looking cool and being different from other brands. In all honesty, to a Russian-speaker the branding of the word “style” on turtleneck collars kind of looks ridiculous (not to mention that it doesn’t actually translate entirely as style in the fashion sense; that would be the word Мода). Although I won’t pretend that this anywhere close to the most accurate comparison, branding Стиль on backpacks and shirts does make me recall the early 2000s fad of non-Chinese-speakers getting tattoos of the Chinese characters for “water” without bothering to verify the translation first.

And then there’s the question of whether or not the replication of certain distinctly Soviet symbols for mass consumption is ethical. While most brands stick to post-Soviet nostalgia, there are quite a few who are beginning to hedge into the territory of Soviet nostalgia. One such Ukrainian designer, Yulia Yefimtchuk, releases jumpsuits with red stars as patches and the distinctly brutalist Soviet yellow lettering spelling “Мы построим новый мир” (translation: we will build a new world). Gosha Rubchinskiy makes sweatshirts with the Soviet propaganda slogan “готов к труду и обороне” (translation: always ready to work and to serve [in the military]). Not to mention the designers who have decided that a sickle and hammer is a cute new pattern, without taking a pause to think about the suffering, oppression, and human rights abuses it is associated with.

Images via here, here, and here.

While I obviously cannot speak for the designer’s choices to release these particular collections, nor can I speak for the entire post-Soviet Eastern Bloc community, I do believe that I’m probably not alone in saying that the carelessness of reproducing clothing with Soviet slogans and symbols is insensitive to the millions of people whose families were directly affected by the Soviet regime. Though the intent is probably not to glorify the USSR regime, the clothing does appear to facilitate an active unawareness of the meanings behind these motifs. And so do, for that matter, gopnik-style clothing brands that mass produce post-Soviet trends for the average Western consumer.

This is not to discount the work of Gosha Rubchinskiy and the like. They have significantly influenced the rise of street style and have done so by creating their own interesting commentary on glamour and focusing it on reproductions of intentionally “poor” images (which is problematic in its own way). The fact of the matter is that all this, in tandem with articles that call the Gosha phenomenon “ugly is the new beautiful” and marketing images of shaved heads with sickle and hammers designs, is difficult to process for those that have been born in and inherited the post-Soviet culture and must now struggle to understand their identity in light of a heavy national history.

Image via

Featured image via