The golden age of hip-hop, much to the chagrin of conservative periodicals and leagues of Concerned Moms, had something of a gangster obsession. Mafia movies were quoted and sampled, the lives of gang members were by turns valorized, eulogized and criticized, and street violence was gorily and glorily recounted. Men—boys conscripted into manhood, some of them—made sense of their lives according to these tales, which were realistic in the sense of giving birth to the reality which bears them out. The faces in the films were largely white, yet they held massive appeal to a generation of young black men. Raekwon’s Only Built for Cuban Linx, the Notorious B.I.G., Jay Z on Reasonable Doubt and American Gangster, Straight Outta Compton…

The appeal of movies which depicted a world of crooked cops, of political (in the realest sense) maneuvering which, if done wrong, could cost your life, of violence, unwanted, but necessitated by the conditions of the world, which depicted the power fantasy of controlling this world, was perhaps obvious. Less obvious was the connection these artists had to another genre, kung-fu movies.

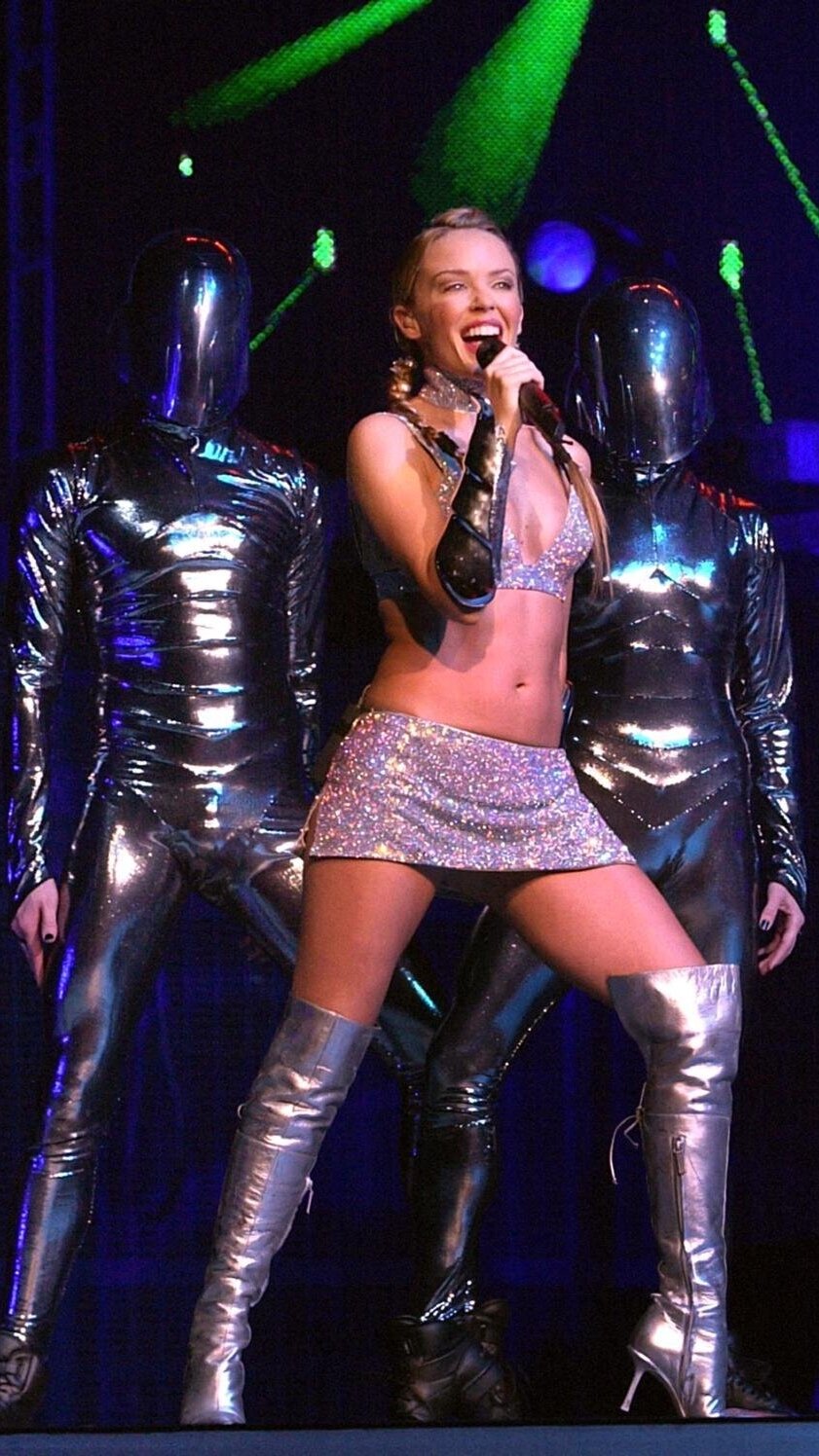

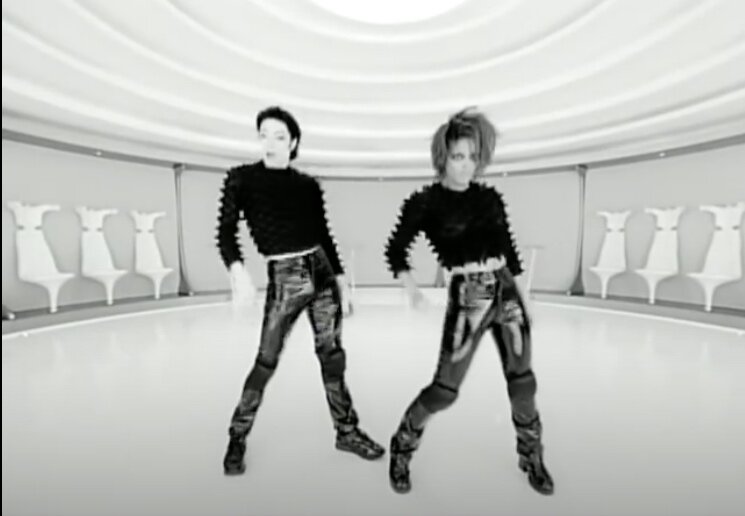

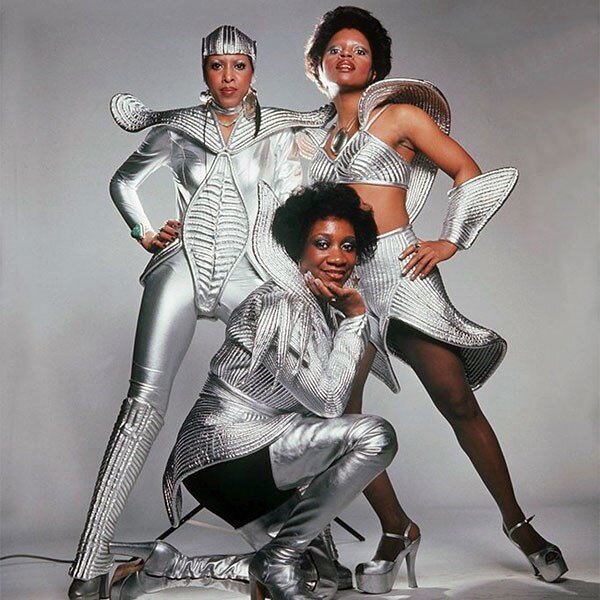

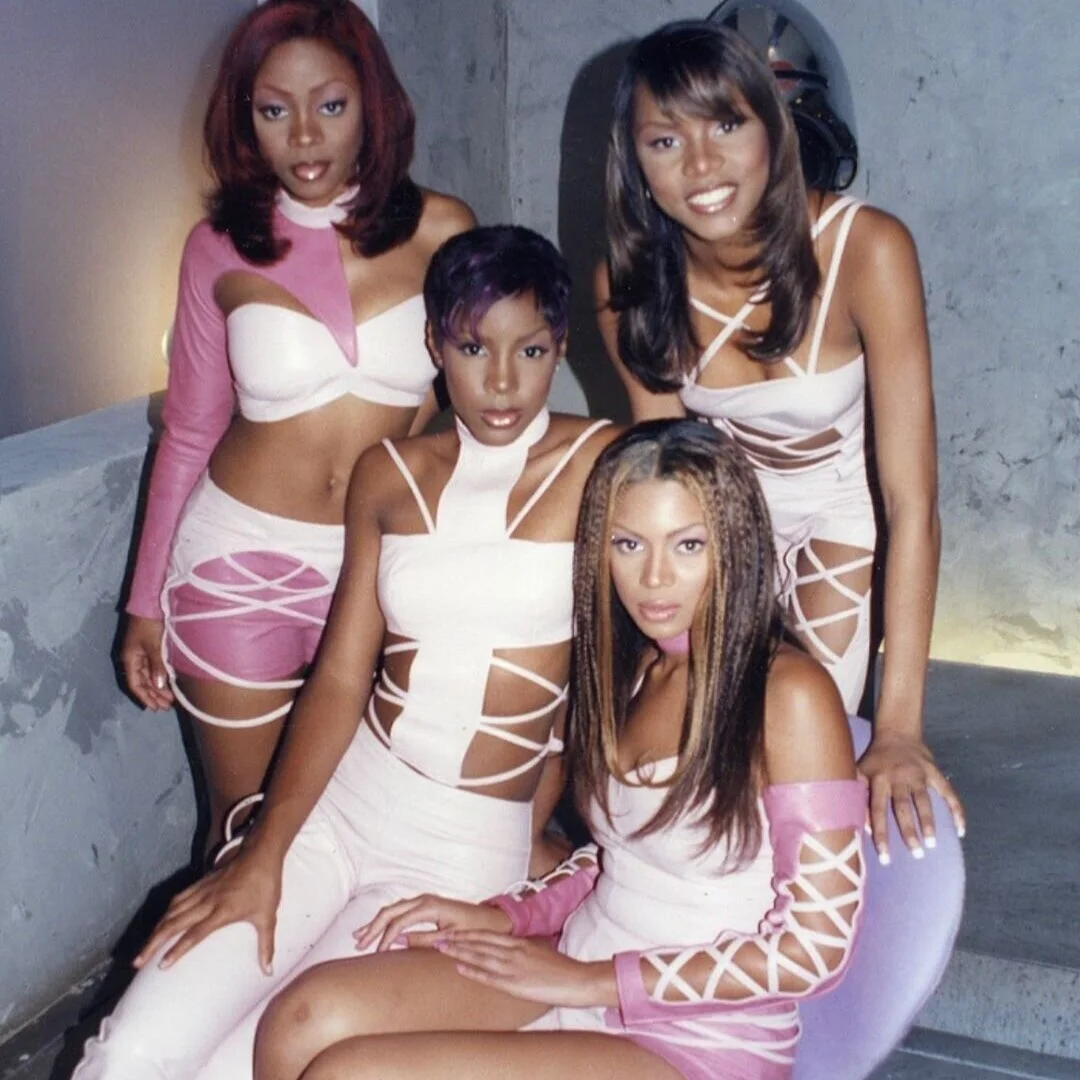

Image via

Imported for cheap from Hong Kong, played on a loop by the struggling theaters around Times Square, and marketed nearly exclusively to minorities, they would soon appear on television as well. Their influence would spread, from Grandmaster Flash to breakdancing moves to, most famously, the Wu-Tang Clan. Kendrick Lamar continues this tradition with his nickname Kung-fu Kenny and in his video for “DNA.”

At the most basic level, kung-fu movies were used as an analogy for rapping itself. Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the Wu-Tang Clan’s first album, is premised on this idea, as are many of their solo albums. In martial arts movies, an apprentice begins by mastering the form, often under the tutelage of an older master. A key element of their training will be sparring with other students and eventually the master (as in GZA’s “Duel of the Iron Mike”). They must create their own unique style in order to become a master (“En garde, I’ll let you try my Wu-Tang style” begins the first track, “Bring Da Ruckus.”) Learning martial arts allows the student to gain control over their situation, to leave behind or ameliorate their troubles. Rapping did the same for the members of Wu-Tang:

Started off on the island, AKA Shaolin /

N***** wildin’, gun shots thrown, the phone dialin’ /

Back in the days, I’m 8 now /

Makin’ a tape now, Rae got a plate now

(“Can It Be All So Simple/Intermission”)

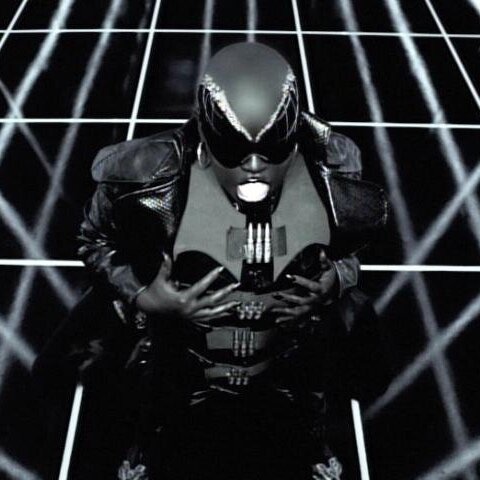

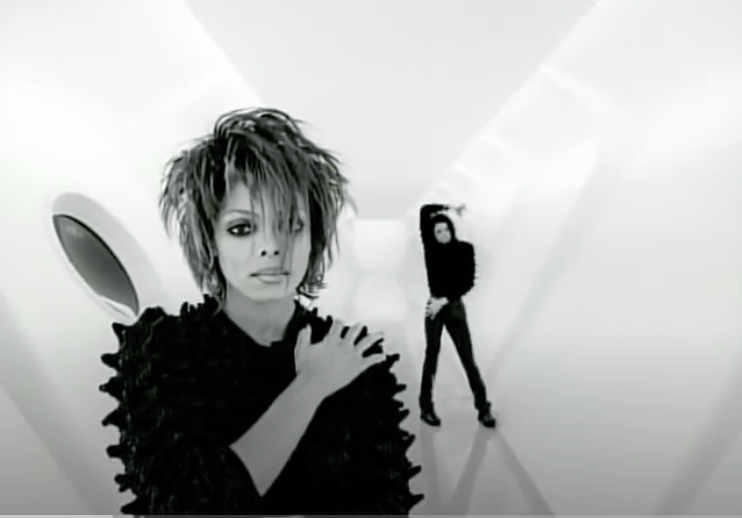

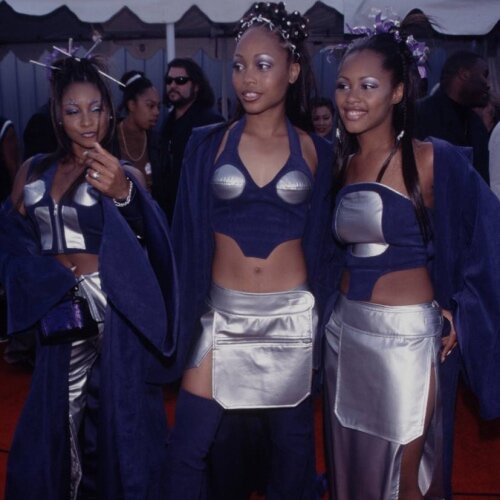

Image via

But this fails to answer the question of why kung-fu movies? It doesn’t explain their appeal in the first place; for that we have to look at the movies themselves. Enter takes its name from a classic of kung-fu cinema, The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, which launched the careers of its director and stars, and secured the place of the Shaw Brothers studio as the leader in Hong Kong imports. The film follows San Te, a young man who becomes involved in a rebellion against the invading Manchus at the behest of his teacher. Upon uncovering the rebellion, the brutal general of the Manchus kills San Te’s family and classmates, leading him to flee the city and seek refuge in a Shaolin temple. There he masters the Shaolin style of martial arts, which, after six years of training to master all 35 “chambers,” he uses to defeat the general and free his hometown. The film ends as he returns to the temple and founds the 36th chamber, which will open the temple to the wider world and teach laymen the art of kung-fu so that they can defend themselves.

The politics of the film are representative of the genre. The hero of a kung-fu movie is also persecuted and at a disadvantage, often by colonizers, sometimes white ones. The heroes of these films, unlike American action films, are also non-white (Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon even features a black star in Jim Kelley, unheard of in mainstream American cinema). Unable to sit down in the face of oppression, our protagonists engage in righteous violence against their persecutors, eventually freeing themselves and their community from the tartar.

The films have a philosophy of violence where it is at once necessary and unwanted. They present a ritualized form of violence—in kung-fu movies there are rules, codes of honor, ceremony in fighting for self-defense—thereby making sense out of what was senseless. The parallel to black liberation for a generation raised in the shadow of the Civil Rights movement hardly needs saying. Like their contemporaries, spaghetti Westerns, kung-fu movies sold the myth of individual liberation through self-cultivation. The messiness of collective action is removed: you can free yourself by training and self-discipline. Mastering yourself amounts to mastery of your situation.

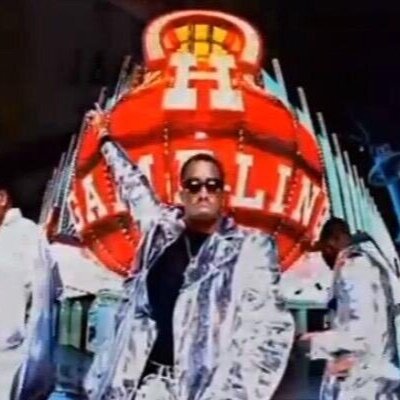

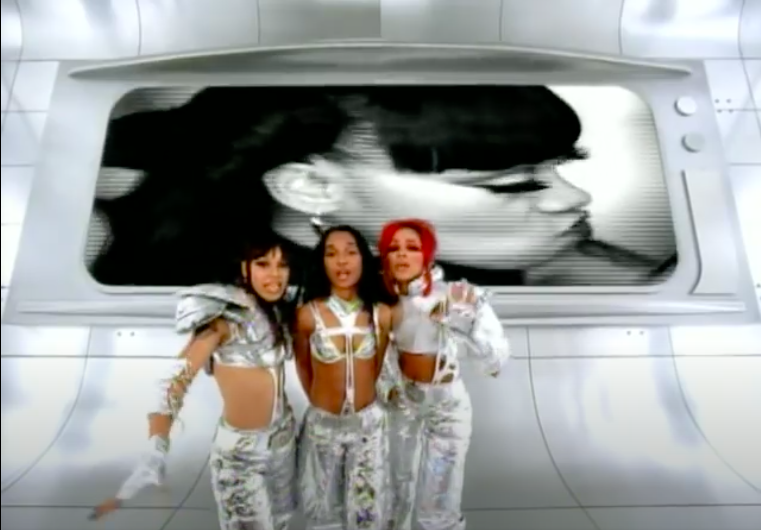

Image via

Perhaps the most successful integration of kung-fu movies is found in GZA’s Liquid Swords, which intermittently samples the 1980 film Shogun Assassin. The film is crucial in creating the world of the album—a world of drug dealers and mules, muggers, shady federal agents and cartoonish violence. GZA is a magnetic presence, bending even the indomitable personalities of his fellow Clan members to his gravitas. His rapping is unrelenting but never rushed, determined and serious, inescapable. Like Rakim, he knows when to effortlessly glide over the beat and when to dig in. He never wrote a simile he didn’t like (on Liquid Swords, “dope sales drop/ like the crash in the Dow Jones stock,” troops are “spread out like crops on a farm,” “cops creep like caterpillars”). The album is nearly perfect in the totality of its mood and GZA’s intransigent flow (excluding Killah Priest’s bonus track “B.I.B.L.E.”, an interesting novelty track which breaks the thematic unity of the album). RZA’s production samples liberally both from Shogun Assassin’s dialogue and futuristic soundtrack to create an exceptionally dark setting, matching GZA’s lyricism.

The film, made from English-dubbed material cut from the first two Lone Wolf and Cub movies, follows father and son Ogami and Daigoro after they are forced to flee their home because Ogami decapitated the Shogun’s son and his wife was murdered by ninja. The Shogun sends various groups to kill the pair, but they are able to rebuff them all. It ends with Ogami killing the Shogun’s brother in the desert.

Shogun Assassin strips the martial arts movie back to its basic components: it is essentially just a series of fight scenes with the minimal plot there to string them along. So much has been cut as to border on incoherence (Why is Ogami’s wife murdered? for instance). Ogami and Daigoro are rarely shown doing anything other than fighting, and when they are resting the respite is brief before agents of the Shogun find them again. There is no safety in their world, no end to the violence; the ending is, likewise, a non-ending which implies that the violence will continue indefinitely. Ogami never kills the Shogun (which would end their persecution), only his brother. The film is pulpy and grotesque – the blood, bright red, erupts from the bodies – and pure camp. The fights, the film knows, are the main attraction. They are poetic and dreamy yet savage and visceral.

Liquid Swords begins and ends with samples from the beginning and end of Shogun Assassin—of Daigoro’s opening monologue and the final words of one of the Masters of Death as his throat is cut, respectively—setting up an analogy between the film and the album. Shogun Assassin sets the tone for GZA’s cold world, of isolation and weariness, where to survive one must become, like Ogami, a demon. The parallels between the songs on Liquid Swords and the samples that frequently begin them is sometimes tenuous, but the effect is quite intentional overall.

Both GZA and Shogun Assassin present hopeless situations; martial arts and rapping don’t help them escape. In this they were outliers. When San Te first confronts the general in The 36th Chamber, his uncle warns him that “One must submit to those who rule.” He asks in response: “Must we and our children yield and conform forever?” Kung-fu movies and the kids who internalized them answered him: “We won’t.”

Featured image via