(The Politics of) Movies About Teens Killing Each Other

You know, that genre?

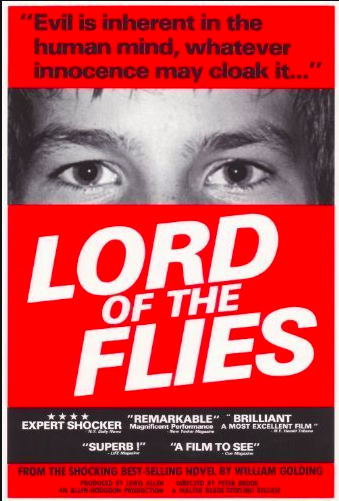

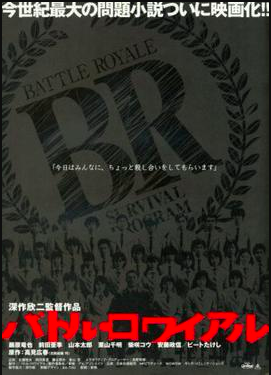

The formative influence is William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and the 1963 film adaptation, and canonical examples are The Hunger Games and Battle Royale, while more fringe examples might include the first few episodes of the Netflix show The 100 and various YA books (many of which have been turned into films) such as Maze Runner.

Lord of the Flies was written in 1954, and deeply informed by the destruction of the second World War. Is this the fundamental nature of humanity? the book asks, with a mind to a young audience freshly equipped with the word “allegory.” A group of British schoolboys (because if the English could be taken to barbarity, anyone could) are stranded on an island when their plane crashes, and they must govern themselves until help arrives. Two older boys, Jack and Ralph, take command: “if we’re sensible, if we do things properly, if we don’t lose our head, we’ll be alright,” Ralph tells the other boys at the beginning. “After all,” Jack adds, “we’re English, not savages!”

Image via

They pretty quickly lose touch with their initially civilized self-governance, as Jack plays on their fear of the “Beastie,” and eventually forms a new tribe. Even the conch, the symbol of civilization, loses its power. He and his boys, who eventually recruit all but Ralph and Piggy, Ralph’s intelligent and tormented second-in-command, cover themselves in paint and perform strange rituals in front of the fire, before killing Simon and later Piggy. Totally atavistic.

Image via

The key difference is that the situation in Lord of the Flies – being stranded – is not contrived by their society. It can thus purport to be a representation of “man in his natural state”; hence why the term Hobbesian is thrown around so often. Not so for the later films, all of which feature a deliberate set-up for the killing. Hunger Games and Battle Royale indict the systems which created these children, not their inherent features. Lord of the Flies, thus, isn’t truly a film about teens killing each other, since they don’t have the explicit goal of actually killing each other, like in Hunger Games and Battle Royale.

Hunger Games doesn’t need much introduction. In a dystopian society two competitors from each of the 12 districts are chosen to fight to the death in a televised spectacle, from which only one can survive. The film is often spoken of as, like Lord of the Flies, an allegory, in this case for the unfair conditions of our “meritocracy” and capitalism. In neither film is subtlety counted as a virtue. In one particularly ripe exchange, Haymitch, the tutor to our protagonists Katniss and Peeta, explains “careers” to them: children from the richer districts who have been trained from birth for the Games. Effie, another advisor to the District 12 kids, assures our heroes that, as a matter of fact, “they don’t receive any special treatment. In fact, they stay in the exact same apartment as you do. And I don’t think they let them have dessert.”

An inspired decision was the inclusion of sponsors. The competitors have two weeks to prepare for the Games, and in that time they have several media appearances to win the support of the public and “sponsors,” who can send helpful items like medicine to you in the arena. This forces the contestants to be likeable to people they hate, to play their game how they intend it to be played, to be “good poors.” Only Katniss is able to find a way to escape their rules, briefly, but even then she only manages to game the system by putting on a show for the cameras. Until then the system they live in is inevitable; all everyone can do is live within it, whether by embracing it like Effie or by small acts of rebellion through kindness like Cinna.

Image via

If the characters in Lord of the Flies are almost purely allegorical – a fact which the movie downplays somewhat – at least in Hunger Games they are allowed to resemble human beings. But the film undermines the empathy we feel for them with poor choices in direction and by failing to build meaningful relationships between the characters. Director Gary Ross shoots even simple dialogue like the most nauseating scenes in The Blair Witch Project, and action is edited in the same way as slower moments: when everything is intense, nothing is. These failures coalesce in the death of Rue, where we see that Katniss cares but don’t particularly know why (they get all of three scenes together) and, as the camera flips wildly between the two as Katniss holds a dying Rue in her arms, we end up feeling more disoriented than sad.

Why teens? This question hovered over me the whole time I was watching these films, and I haven’t been able to come up with a good answer yet. Other than Mel Gibson’s Mad Max, I can’t think of any battle royale-type movies starring and targeting adults (although I think it’s fair to say Mad Max’s demographic skews male and younger). One suggestion is all the fighting is kind of like high school, or somehow a representation of cutthroat teenage social dynamics. And while I don’t remember high school as particularly Thunderdomey, there is something to be said for the idea that these movies are just like any other teen movie, but with the melodrama turned way up. The plethora of YA novels left in the wake of Hunger Games also suggests that the genre (loosely defined) speaks to the desire to feel special and important, and even a little victimized.

Battle Royale is political only insofar as human relationships are. There is no outside world depicted in it, no larger political struggle at work, like in Hunger Games. All we know is that some economic collapse happened and youth delinquency skyrocketed, so the government created a law which randomly selects one class of ninth graders each year to participate in a battle royale. But this is no world-halting spectacle: there are no cameras on the island, and the kids didn’t even know of the event until they were chosen. The violence is senseless, both for them and the audience. They have no two week period to come to terms with their fate, no public selection process where they can say goodbye to their friends and family.

Image via

We find them on a bus, thinking they are headed to a school field trip, until they are knocked out and wake up in a classroom on a deserted island. Their old teacher, Kitano, surrounded by military guards, shows them an instructional video which tells them they will be given a pack with a random weapon (ranging from guns to a pot lid) and a necklace which tracks their movement and explodes when they stray too far or try to take it off. They are told if one person does not emerge after three days, all remaining will die. And it is here that we realize Battle Royale will not play by the polite rules of Lord of the Flies or Hunger Games.

Before the event even starts – during the presumed safety of the instructional video no less – Kitano kills one of the girls for talking. The best friend of the protagonist then has his necklace blown up, killing him as well. Before he dies, his necklace beeps menacingly, and he stumbles around the classroom looking for help; but the friendships are already over, and he’s pushed away by his classmates. He makes the protagonist, Nanahara, promise to protect Noriko, who the now dead friend had a crush on.

They are sent out one by one onto the island along with two dangerous-seeming outsiders (victors from previous years). Battle Royale then tells a series of vignettes, miniature tragedies and bleak comedies – stories of friendships tested by suspicion and paranoia, and forged through sympathy, of grisly deaths and an improbable number of gunshots survived – mainly following Nanahara and Noriko. These vignettes are masterpieces of condensed storytelling. In one, Nanahara is injured, but luckily gets rescued by five girls living in the island’s lighthouse. A shy girl, who doesn’t like the idea of a boy living with them, intends to poison Nanahara at lunch, but her friend grabs his meal instead and dies while they all watch. The suspicion over who killed her quickly destroys their idyll and they kill each other in a gun fight while old school rivalries and petty grudges are dug up.

The film has a reputation for nihilism, which isn’t quite deserved. Ultimately, it is the love and trust between Nanahara and Noriko, and the friendship they come to feel for Kawada, one of the previous winners, that allows them all to escape. Nonetheless, it is true that those quickest to trust are the first to go: in a cruel world cruelty is rewarded. This says at least as much about the adults who created this world as it does the kids who inhabit it, however. The film suggests that asking whether the ability to kill was inside them all along is asking the wrong question. “There are some things you’re better off not knowing,” Kawada says.

Image via

Towards the end of the movie only Nanahara, Noriko and Kawada remain, and Kawada has found a way to trick the government into thinking the other two are dead. Their old teacher Kitano figures this out, and stays behind on the island to confront them. When they meet him in the old government headquarters, he aims his gun at Noriko and tells her to shoot him before he shoots her. Noriko and Nanahara have thus far escaped relatively innocent: they have managed to avoid killing anyone. We now understand why Kitano is doing this. He needs Noriko, who he has always had a soft spot for, to understand him, to feel what he has felt and live with the consequences like he has.

Maybe this is the only messed up way he knows how. Nanahara eventually fires at him, but doesn’t kill him. The teacher pulls the trigger, causing both Nanahara and Noriko to shoot at him, finally causing fatal damage. Kitano was holding a water gun. Nanahara, at least, has found meaning in all this: he has fulfilled his promise to protect Noriko.

Perhaps this test showed him what he was truly capable of, good and bad.

Perhaps he would’ve been better off not knowing.